The discovery of a new triple asteroid – (93) Minerva

A fantastic night at Keck observatory – A follow-up

August 16, 2009217P/LINEAR is breaking up or giving birth?

August 24, 2009Hello,

So I was quite mysterious after my observations at Keck Observatory, and I briefly mentioned that we discovered something interesting during the night. I will give a little bit more details in this blog since the IAU circular announcing the result is about to be published. To summarize, the high angular resolution images provided by the Keck Adaptive Optics system revealed that the asteroid 93 Minerva possesses 2 tiny km-sized moons in orbit around the large 140-km primary.

As you may reckon from one of my previous posts, the goal of our observing program was to look for binary asteroid in the S-type class, meaning asteroid with companion(s) which are composed of “rocky” (or siliceous) material. We know ~175 binary asteroids and less than 50 of them were imaged using adaptive optics systems available on ground-based telescopes or Hubble Space Telescope. After discussions with my colleagues, we noticed that no S-type asteroids were known to have a small km-sized companion orbiting far away from the primary (7-12 x radius primary) whereas numerous C-type binary asteroids (primitive composition) with these characteristics are known. I therefore decided to ask for telescope time at Keck Observatory in March 2009 to search for S-type binary asteroids.

A few months ago, we got an email from the UC-observatory Telescope Allocation Committee announcing that we go telescope time for this program. One night was scheduled to us on Aug 15 HST (so Aug 16 in Universal time) and I flew to Hawaii, Big Island to conduct these observations. Luckily, despite an uncertain beginning, the weather got excellent and the atmospheric conditions and turbulence strength were good, a.k.a. the visible seeing was estimated to 0.7 arcsec in visible light.

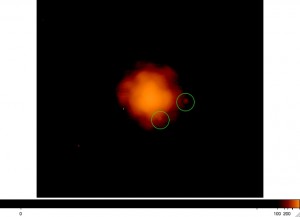

The key during this kind of observing nights is to observe as many asteroids as possible, process the data while observing to be able to identify if a secondary companion is detected. I was the only visitor astronomer so my night was very intense. Over the second half of the night, I found out that I underestimated the on-sky efficiency of the Keck AO system and was bout to get some gaps in my list of S-type asteroids. I decided to use this available time to observe large C-type asteroids not yet observed with adaptive Optics systems. At 13:36 UT, I observed 93 Minerva and shortly after processing the data noticed the presence of a small dot at 0.4 arcsec and 3 o’clock (270 deg). Because I did not see this “artifact” on my other data and I noticed also an Airy feature around it (a ring due to the diffraction of the telescope), I interpreted that this could be a companion. I reobserved it 8 min later and detect the companion again, but also a smaller one at 0.25 arcsec and 209 deg. I was certain that we were observing the asteroid since the primary was resolved displaying a spherical projected shape of 140 km in diameter.

Low level intensity of an observation of the main-belt asteroid (93) Minerva. The two green circles indicate the positions of the two moons that we discovered during this night.

After having recorded a PSF star to confirm the absence of artifacts at these positions, images at other wavelength range, I concluded that we indeed discovered a new triple asteroid system. The two moons are 4 and 3 km in size and the projected separation corresponds to 630 km (8.8 x Rprimary) and 380 km (5.2 x Rprimary) respectively.

- How many triple asteroids systems do we know?

Our group discovered the first triple asteroid system in 2005, it was (87) Sylvia and its two companions Romulus and Remus using the VLT/NACO. Since then we know than (45) Eugenia and (216) Kleopatra also main-belt asteroids, possess two moonlets. Our group discovered all these triple asteroid systems over the past 4 years. There are a few triple asteroids in the Near-Earth Asteroids (2 of them) and in the TransNeptunian Object populations (2 of them including Pluto).

- Is this observation useful or purely anecdotic?

The more the merrier! and the more triple systems we know, the more informaton we will collect useful to understand how they formed and evolved. In our Press-releases from ESO and UC-Berkeley and the article published in Nature Journal in Aug 2005, we mentioned that the the 87 Sylvia triple system was most probably formed through the disruptive collision of a parent asteroid, with the new primary resulting from accretion of fragments, while the moonlets are formed from the debris. It should be interesting to compare these triple systems to see if they can share a common scenario formation.

Artist rendering of the triple system: Romulus, Sylvia, and Remus. This is the first triple asteroid system discovered - two small asteroids orbiting a larger one known since 1866 as 87 Sylvia. Because 87 Sylvia was named after Rhea Sylvia, the mythical mother of the founders of Rome, our team decided to name the twin moons after those founders: Romulus and Remus.

- Why did we discover this triple asteroid only in 2009?

The improved AO system at Keck provides the best sensitivity to detect these kind of multiple asteroid systems. It is offered in this configuration with this capabilities for two years now. Our observations show that without the recent improvement in quality of two moons would not have been detected. Additionally, we observed ~500 asteroids with several AO systems on 8-10m class telescopes over the past 6 years and (93) Minerva had never been observed previously.

The next step will be to record more data to derive the orbital parameters of the satellites. I will ask some colleagues who have access to the Keck telescope over the next 3 months if they want to contribute since I don’t have myself telescope time. The asteroid will be at its opposition on Oct 16 2009, so there are a lot of opportunities to re-observe the system in better conditions this year.

At a shorter term, I wrote an IAU circular to announce our discovery. Hopefully it will be published soon. My ex-student Brent Macomber, my two colleagues from IMCCE (J. Berthier and F. Vachier) and my colleague from University of Tennessee at Knoxville (J.P. Emery) are co-authors since they were involved in the proposal writing and help me preparing the observations.

I am in vacation until August 26 so I will write rarely on this blog until then. However, I will read your comments and questions if you have some.

Clear Skies

Franck Marchis

2 Comments

Has separation data been acquired (or estimated) for the components of 216 Kleopatra?

— Kevin Heider

Kevin,

yes it has been acquired and measured. See for instance our IAU circular. http://www.cfa.harvard.edu/iauc/08900/08980.html#Item1

“The new AO data show

additionally the presence of a about 5-km-diameter companion at

0″.72 (projected distance of 650 km) in p.a. 322 deg, detected in

every image recorded over the 5.5-hr baseline. Careful analysis of

the last set of data indicates the presence of a second satellite,

smaller (about 3 km) and located closer to the primary at an

apparent distance of 380 km (0”.42) in p.a. 333 deg. “