The End of Kepler – It’s not over yet but it will happen soon.

Capturing a Snapshot of Pluto’s Atmosphere. The Story of an Occultation

August 19, 2018

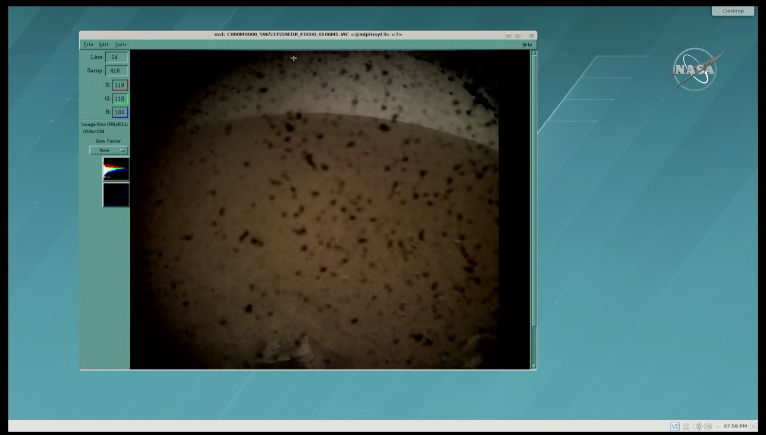

Welcome Insight lander, you are on Mars!

November 26, 2018The Kepler space telescope, which was launched in March 2009, is the tenth NASA Discovery mission and the first dedicated to searching for and studying exoplanets. It was scheduled to operate for about four years, but is still active almost a decade later and after its scientific objectives changed when it was renamed the K2 mission. Despite these tremendous successes, scientists are now concerned about the health of the spacecraft, and a team of engineers and astronomers are working together in hopes of extending the spacecraft’s data-gathering capabilities for as long as possible.

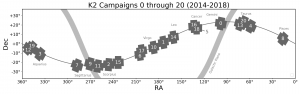

In May 2013, loss of a second reaction wheel should have ended the mission, but Kepler was rebooted, renamed the K2 mission, and given a new goal: use the telescope’s high-photometric precision to observe stars and solar system objects located along the ecliptic. Each cycle of observation, which is known technically as a campaign, lasts about eighty days and consists of observing one patch of the sky.

The spacecraft, which has already overshot its nominal lifetime by a factor of two, is currently in Campaign 19 and still collecting valuable scientific data. We got good news last week when the Kepler team managed to contact the spacecraft and determined that it seemed to be healthy and in fine point mode fine point mode (meaning that the spacecraft has pointed to the correct FOV and does not have any motion that could degrade the data quality). The next attempt at contact is scheduled for September 26, but until then there is no way to know what is going on up there in the distant and cold realm of outer space.

The Kepler team has good reason to be worried about the health of the spacecraft because in the middle of Campaign 18 its fuel pressure dropped so fast that it went into a protective safe mode. At this time the spacecraft used its reaction wheel to stabilize itself and point its antenna toward Earth, which allowed for contact but stopped the acquisition of new data. NASA used the Deep Space Network Antenna to download two months of data, including engineering stats that gave it information on the state of the spacecraft. The engineers concluded that the drop in pressure was not as serious or dramatic as previously feared and decided to re-initiate Campaign 19 to get more science.

K2 Campaigns across the ecliptic. (credit: NASA)

One of the many difficulties of working in space is that there’s no way to predict how and when a spacecraft’s life will end. The Kepler team is certain that the spacecraft will not stop abruptly like a car running out of gas on a freeway, but instead will show signs of a malfunction that engineers will have to detect, understand, and fix from 150 million kilometers away.

Prior space missions dedicated to observing one or more solar system bodies have had endings far more grandiose than anything Kepler is likely to experience. In 1995, NASA decided to plunge the Galileo spacecraft into the dense atmosphere of Jupiter. More recently, after nineteen years in space, the Cassini mission, which was running out of fuel, was ended up in the atmosphere of Saturn. Spacecraft dedicated to the exploration of small bodies like asteroids or comets are landed on or, more correctly, slow motion crashed into their surface. Those dramatic endings happen because unique scientific observations can be collected during a very close approach, before the spacecraft is obliterated by colliding with the surface of the body it is studying.

Cassini’s Grand Finale from an artistic representation. The spacecraft is breaking apart and melting in Saturn’s atmosphere during its descent. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

In other cases, the ability of the spacecraft to communicate with Earth is so degraded by distance that contact becomes impossible. The International Cometary Explorer (ICE) spacecraft, which was launched in 1978, drifted away from Earth after passing through the plasma tail of comet P21/Giacobini-Zinner. That’s why NASA ended this mission in May 1997.

The Kepler spacecraft is facing two big challenges.

Because it’s orbiting the sun as well as Earth, Kepler is moving away from us. Today it’s at 1.1AU from Earth and every two weeks this distance increases by 0.01 AU (1.5 million kilometers). As of today the Kepler team needs to request access to the DSN network’s 40-m antenna in Canberra to talk to the spacecraft. In several months, Kepler will be so far away that we will be unable to communicate with it at all. At that point, Kepler will drift away, unable to send any more data to us. For the moment, the K2 mission web page lists Campaign 20 (until Jan 05 2019) but Campaign 21 is being planned already, so there is hope that we will be able to contact the spacecraft until spring 2019 at least.

The spacecraft may not survive until early 2019, since it shows clear signs of degradation. One especially urgent concern is the propulsion system used to orient Kepler, whose thrusters were behaving erratically in C19. The team identified the problem as coming from one thruster, which poses this question: if the spacecraft is running on only one thruster, how long can that thruster possibly last?

Every week a skeleton team composed of two engineers at Ball Aerospace, at few people at the Mission Operations Center at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado, and three SETI Institute and NASA Ames scientists assess the state of the spacecraft and decide what to do with the data on board. Attempts to communicate with Kepler to determine its status are possible but sporadic, so any decision may have to be taken quickly if the degradation cascades and the spacecraft becomes uncontrollable. At this point, the goal of the Kepler team will be to save the data on board. If and when this dire scenario occurs, the head engineer at Ball Aerospace will make recommendations about ending the spacecraft’s life, NASA Ames program manager will take a decision and NASA HQ will make the announcement. Right now, it’s impossible to predict when this might happen.

Let’s keep in mind that even though the spacecraft’s life will be over, the mission will continue. The science and engineering data generated by the last campaign will need to be documented and archived. The science pipeline center will continue to process all the data collected by K2, which will allow researchers around the world to conduct their science. We can expect new exoplanets to be detected and announced next year, even after the mission’s official end date, probably in 2019.

And what’s going to happen to Kepler itself? It will always be remembered as eloquent testimony to human ingenuity and our willingness to explore and understand our galaxy. This spacecraft alone has discovered more than 2,600 exoplanets, almost 70% of the known exoplanets so far.

Motion of the Kepler spacecraft in the rotating frame (Earth is stationary) showing the horseshoe orbit of the spacescraft and its return at proximity of Earth in the 2070s (credits: Tony Dunn, Orbitsimulator.com)

Kepler will continue to orbit the sun, but the remaining reaction wheels will not be able to stabilize it for more than a few months. In 41 to 45 years, when it returns to the vicinity of Earth, it may be spinning erratically on itself, making communication quite difficult.

Why would we want to communicate with it again? A team of amateur radio-astronomers and scientists were interested in using the ISSE/ICE spacecraft to explore comets in 2017 and 2018. With the help of NASA, they managed to contact the ISSE/ICE mission in May 2014 when it had a close encounter with Earth and commanded the probe to switch its communication mode. The reboot failed because of a malfunction of the old thrusters. In the 2060s, a group of engineers and scientists may want to try the same with Kepler.

Capture of a debris in orbit around Earth using RemoveDEBRIS, an experimental satellite equipped with a net.

Maybe by then, our technology will have progressed to the point where it will be possible to capture the Kepler Space telescope and bring it back to Earth. If so, it will be an amazing object to view in a museum dedicated to the history of aviation and spaceflight. This is, after all, the first space telescope dedicated to the search for exoplanets, and one that has radically changed the way we perceive our galaxy. It opened our eyes to the large number of worlds out there, waiting to be explored. Clearly, it deserves a special place here on Earth, the planet that launched it into the cosmos, and in the mind and heart of the species that built it and sent it on its astonishing mission of discovery.

Clear Skies

Franck Marchis