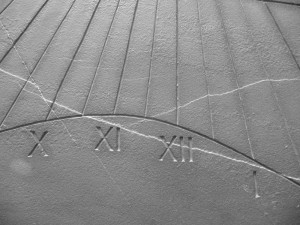

A Sundial cast in stone

My Grand Mother and Galileo

December 3, 2009

Stars older than the universe. How can this possibly be?

December 15, 2009Today I was all day long in a Time Management training course, organized by ESO. You might wonder why on earth an astronomer should take a course in time management… but actually, more and more (especially in big organizations as ESO is) astronomers (as they come of age) get also some managerial responsibilities. This is very much the case when they act as project scientists and have to interact with engineers, who are used to proceed in a very structured way (as opposed to scientists, who [often] know where they are but not where they are heading to). One of the most important aspects is how you manage time. And thinking about this it occurred to me that last August, during my summer vacations in Northern Italy, I had done something about time management. Not the way the trainer has told us today, though.

In fact, starting in the early ’90, I have designed and constructed a number of sundials (actually, as an exercise of spherical trigonometry, I had also derived the equations that govern the drawings of a solar clock). My father Giovanni happens to be a professional sculptor, and has spent all of his life mainly working on stone. So, occasionally, we have manufactured some sundial cast in stone (if you wish this is another way of mixing astronomy and art). Sundials are usually painted on walls, but having them deeply engraved in stone makes them practically everlasting and adds to the concept that their mechanism (in contrast to any mechanical/electronic clock) will never stop working (well, actually it will, as soon as the sun will become a red giant. But Earth will have disappeared by that time…). Some years ago, for the birth of their last child, a family of friends had commissioned us a solar clock, and they wanted something special. And by chance in the atelier of my father there was a slab of stone that had been found along a creek. It had the peculiarity that ice had broken it into two almost identical pieces, a few centimeters think, with almost parallel surfaces.

In the sundials we had done before, besides the dial drawing, my father had sculpted figures like bats (to indicate the night), a field of wheat (for the summer) or his view of the Hyakutake comet (in a sundial made in 1997, when the comet had passed close to the sun). But this time he said Nature had done a better job and his hand should not dare to alter its wonderful shape and textures. In his view, the slab was a sculpture in itself (lately, while sculpting, he has been trying to preserve the imprint of nature, following her guidelines and without altering them too much). Our friends did not have yet a proper wall where to place it, so the stone remained dormant in my father’s atelier, waiting to see the light. The time was mature last summer, when their new house was in a stage where we could start working on it. And so, in one hot day in August, armed with my old device to estimate the inclination of the wall with respect to the east-west line, I did a few measurements. The wall turned out to be declinant by only 7.8 degrees, so that the equinoctial line would be only slightly inclined with respect to the horizon.

After measuring the latitude of the site, I entered the data in a simple computer program I wrote many years ago and I produced the numbers which I then traced directly on the slab, in the fresh shade of my father’s lab (note that the same calculations can be done “by hand. Speaking of time management, it just takes longer…). The sundials we had done so far were drawn on rectangular, machine-cut slabs, and there the task was easy. In this case the shape of the stone was all but rectangular, although it certainly had an elegant geometry, whose curves would well harmonize with the human-made analemn. After a few attempts, we finally found what seemed to be a good scaling and positioning of the dial. After tracing the lines (both straight and curved) with a hard pencil, my father used a few hundred gram hammer and a chisel to give a first pass, engraving the lines to a depth of roughly a millimeter. Then, with a very fast rotating diamondwork disk cooled with water he has deepened the straight lines (hours and equinoctial line). For the curved ones he has done the same, but with a hand tool. Finally, he has engraved our names and the date (GPN MMIX).

All this took less than an afternoon and the day after, just before sunset, the slab was mounted on the wall. But the sundial was left “silent”, that is without the gnomon (the small stick that casts the shadow). For this I had asked my good old and ingenious friend Armando (you might remember he has done also the big Pendulum for the Shadow of the Earth). I usually build the gnomon myself, but for this particular one we wanted to have something very special. And special it was. In fact, he managed to have it in stainless steel, with a laser-cut star at the top, giving a very high-tech look to the whole thing. Contrarily to what one would expect there is no contrast between the shapes carved by nature and this metallic artifact. The gnomon is now ready and just waits to be put in place. This is going to happen around the winter solstice, when we will properly celebrate the event. From then on the sundial will start marking the time for the years to come.

Gee, it’s past midnight!! Talking about time, it is now time to go to bed. Tomorrow morning I’m back in the time management course. I’d better go to get some sleep. Good night.