Once covered, now revealed

Both wind-carved *and* ancient

February 1, 2021

Historical wind and modern wind

May 3, 2022March 29, 2021

Mars is such a fun place. We’re finding out that it’s got oodles of geologic history. It’s got layers deposited by wind and water and lava, altered in place (sometimes many times), then eroded again by wind and water and lava. It’s never boring.

My favorite, of course, is the wind. I really like modern dunes that are now crawling across the surface and the wind blows their sand along. But I also like old ones that preserve information about the wind patterns from a long time ago.

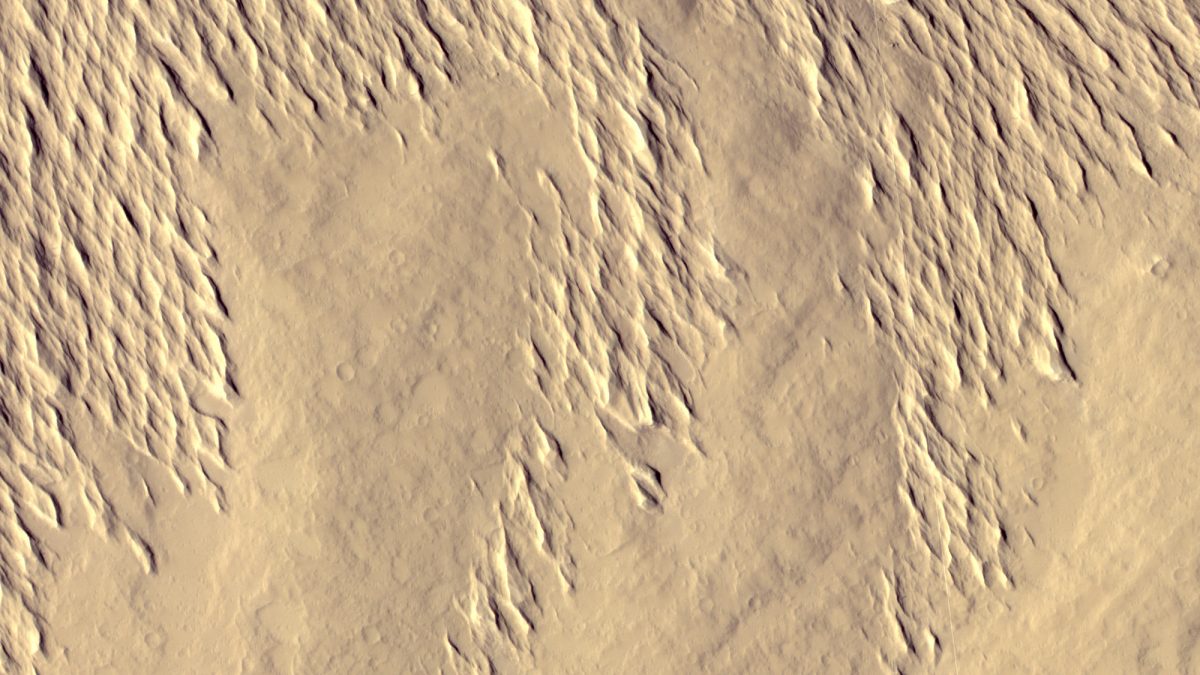

This is ESP_068039_1780, a really spectacular HiRISE image that shows a lot of wind erosion has happened (as always, click to see a bigger version):

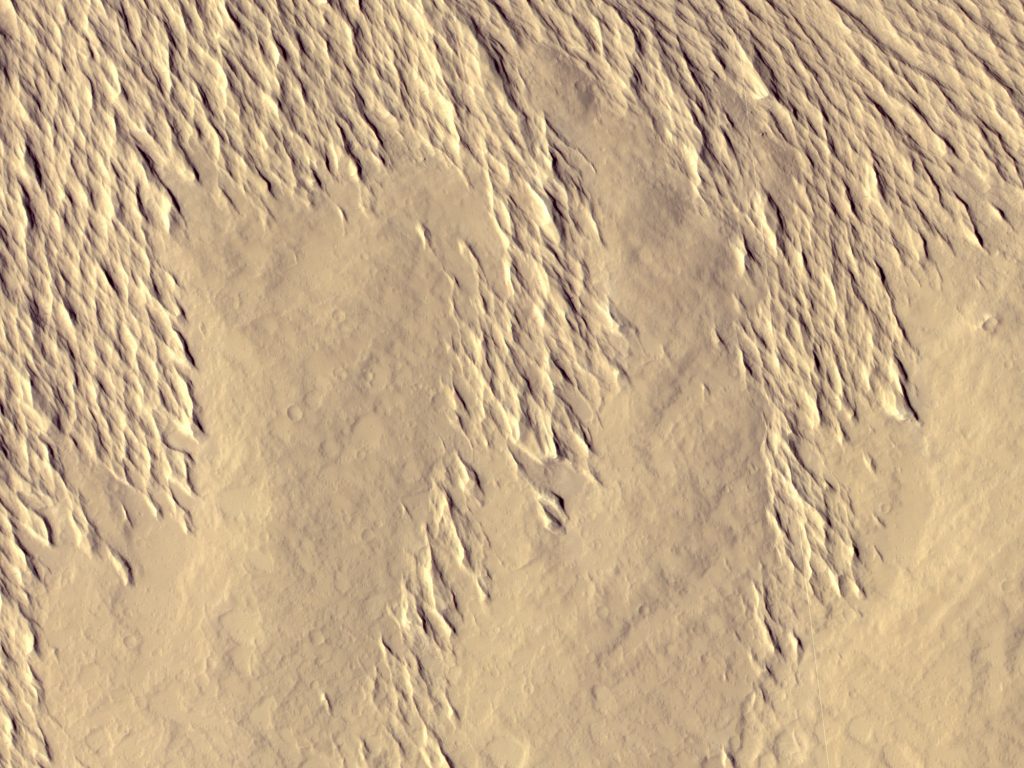

ESP_068039_1780, a wind-carved landscape. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

This is in the Medusa Fossae Formation, perhaps the most deeply wind-scoured region on the planet. Recent work suggests that it may be the largest source of airborne dust on Mars. The best analog for this on Earth is the Bodélé Depression in Chad, which is the largest modern source of natural mineral dust on our planet.

However, unlike the Bodélé Depression, the Medusa Fossae Formation (MFF) may not currently be a major source of dust on Mars. Or at least, it’s not one of the major regions where dust storms form today. Scouring all that surface requires loose sand to do the scrubbing, and these days there aren’t many serious dune fields or other signs of active sand piled up in the region. So it’s possible that this area underwent a major scour a long time ago (billions of years maybe), and the sand has long since moved on to some other career path.

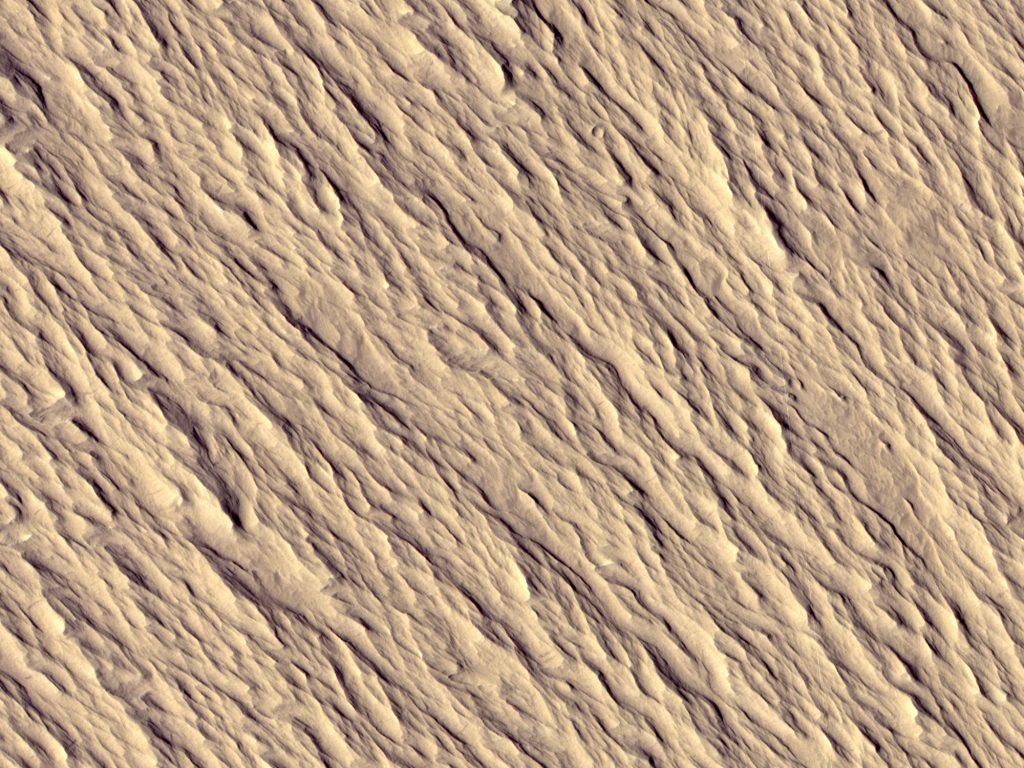

But just look at what that sand was able to do. Here’s a bit of the color part of the image, from the bottom middle of the above image:

Portion of HiRISE image ESP_068039_1780, with a view of 1 x 0.75 km (0.62 x 0.47 mi). All the texture here is made by the wind (except the little 12 m crater near the top). Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

These ridges, known as yardangs, just go on and on. If you wanted to walk northwest or southeast you’d have a nice stroll, but if you were trying to go pretty much any other direction, you’d get quite a workout.

It’s pretty clear that the stuff that’s been carved up is part of a large layer of sediment that once covered most, or maybe all, of the whole HiRISE image. It was eroded from the high ground more quickly (the wind is accelerated as it blows up hills, making it a more effective eroding agent). So now we see mostly bare mesa tops, between which is a vast sea of the grooved, fluted yardangs.

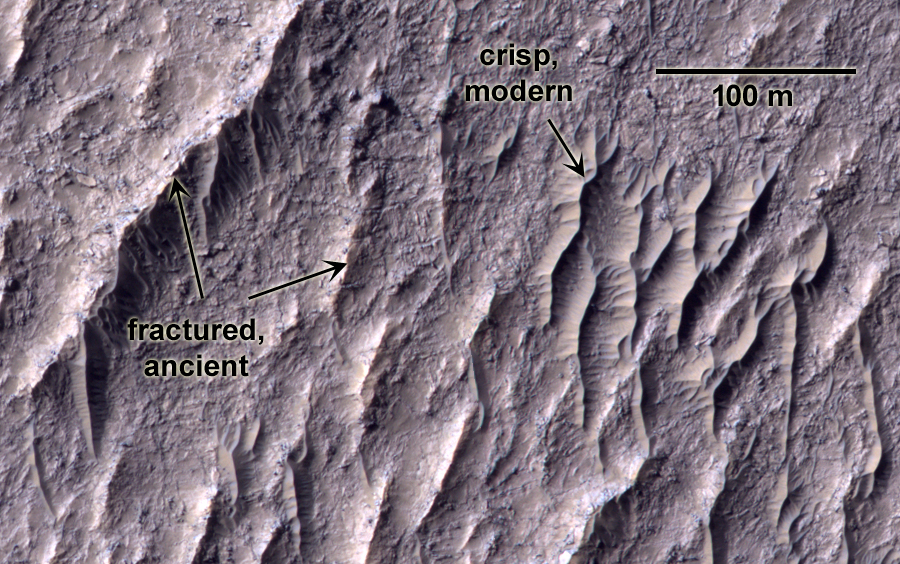

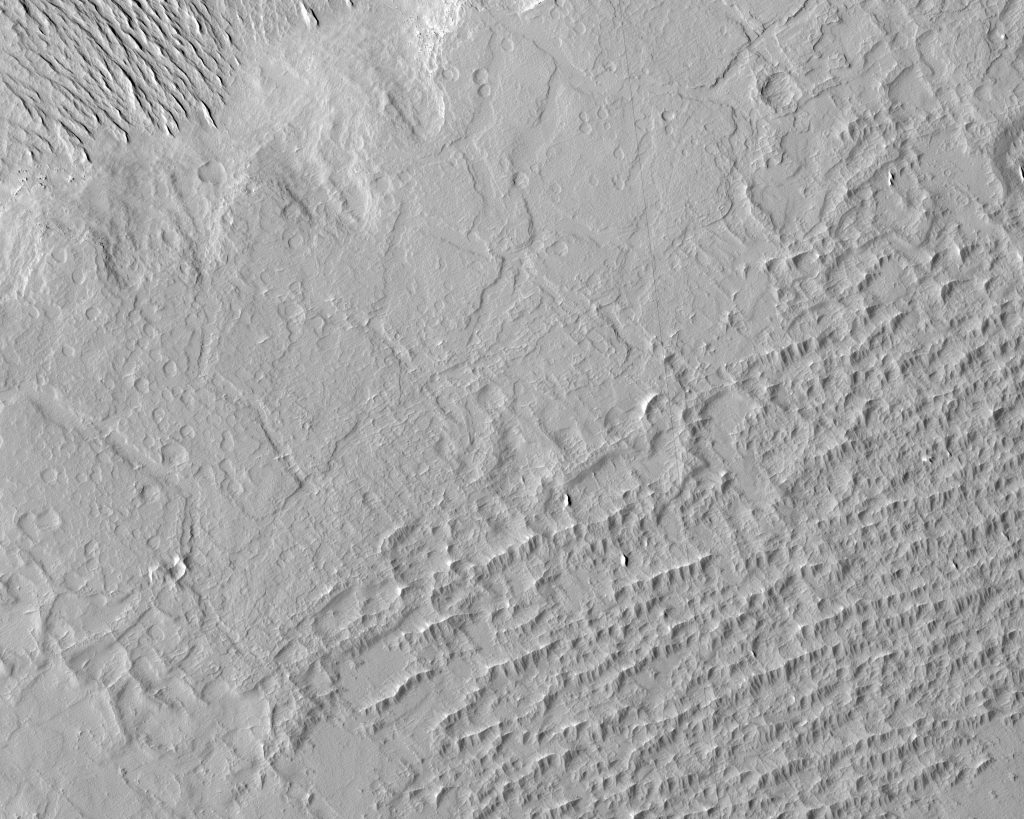

Here’s a transition from a low-lying area (at the top) to smoother high ground (at the bottom):

Portion of HiRISE image ESP_068039_1780, with a view of 1 x 0.75 km (0.62 x 0.47 mi). The bare hills of the mesa at the bottom have been scoured clean of the yardangs. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

See how the bare ground has craters on it, but the fluted yardangs don’t have many craters? The bare ground of the mesa stood around for a long time, getting hit by enough meteors to make all those craters. That ground is too hard for the wind to whittle, at least on the timescale we see here. But the stuff that makes up the eroding layer is so soft that it cannot hold on to many craters – they get scoured off too quickly.

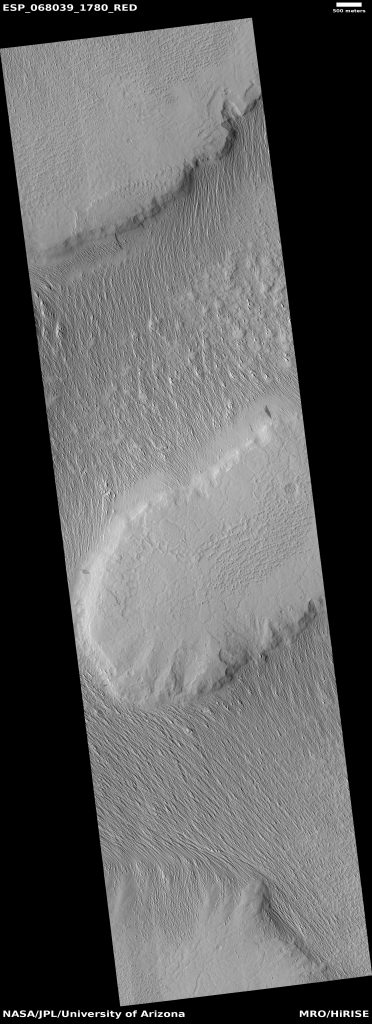

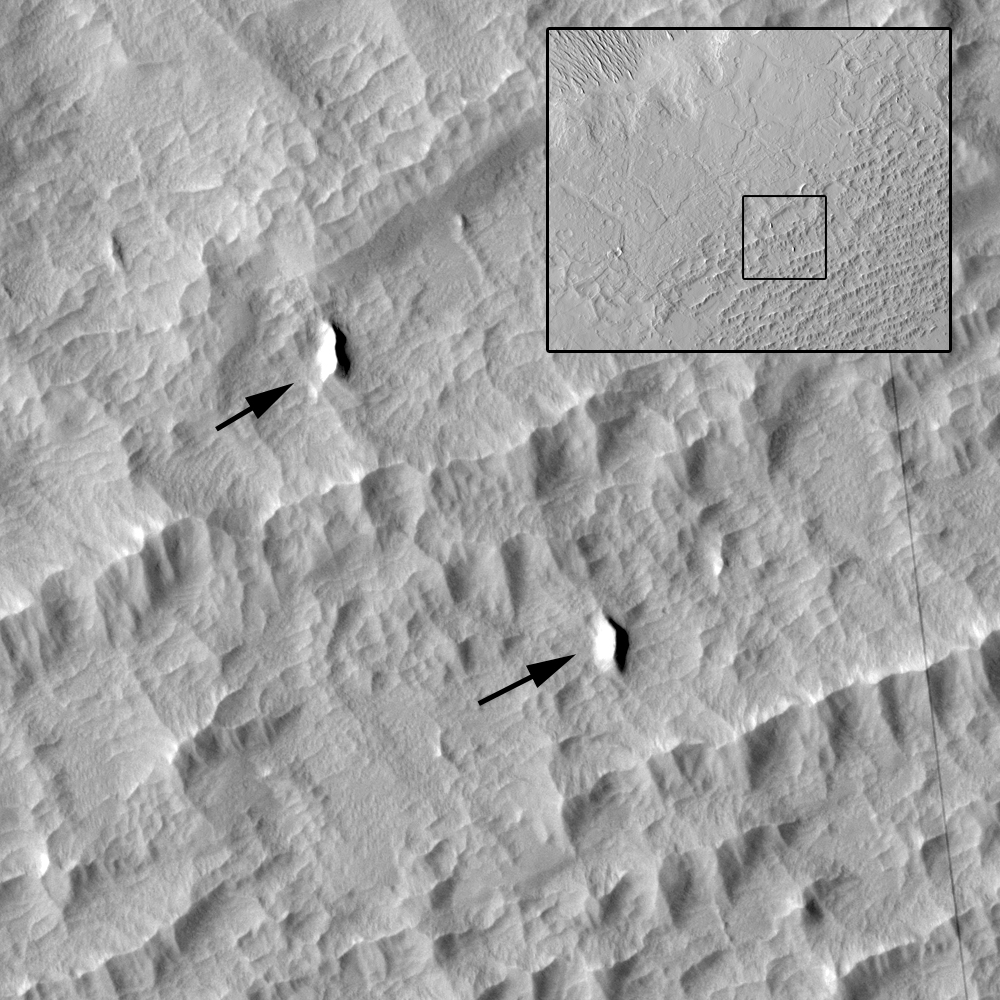

I know that the scoured, yardang-filled material once covered the mesas as well, because here and there are bits of it left. And, best of all, they once covered a field of windblown bedforms! Look:

Portion of HiRISE image ESP_068039_1780, with a view of 2.5x 2 km (1.55 x 1.24 mi). There was a field of bedforms at the top of the mesa (lower right). Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

At the top left of the above image (sorry, the color strip didn’t cover this part of the image) are the yardang-covered lowlands. Over the rest of the view, the mesa rises to a height ~200 m (~660 ft) above the lowlands. And at the lower right are some fossil bedforms. Once they were made by the wind of loose sand. Maybe they were dunes, or maybe they were the mysterious Martian TARs.

In a few small spots there are some remnants of the yardang-covered terrain that once covered the mesa. They stand out as sharp features aligned the same way as the rest of the yardangs. Here’s a closer look at a couple of them, pointed out by black arrows:

Portion of HiRISE image ESP_068039_1780, with a view of 500 x 500 m (0.31 x 0.31 mi). Black arrows point out the location of yardangs, showing that even the mesa top was once covered by this wind-eroded material. It even buried this field of windblown stuff underneath it! The inset shows the location of this within the previous image. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

It’s pretty cool. These yardangs appear to have been carved by a wind blowing from the lower right to upper left. That’s a southerly wind, opposite of the current dominant wind in most equatorial areas on Mars. Why was the wind so different? How old are the bedforms that the soft material covered up? How long did the soft, erodible material cover the mesa tops? I just have so many questions!!