The new crater

Hills with tails

June 8, 2020

Those crazy southern polar dunes

July 17, 2020June 15, 2020

Utopia Planitia is an ancient plain in the northern lowlands of Mars, thought to be made of volcanic rocks that were buried, more than 3 billion years ago, by sediments carried by water coming down from the southern highlands (this is the wonderfully vast late Hesperian lowland unit (“lHl”) of Tanaka et al., 2014). After the sediments piled up, most of the surface hasn’t had a lot happen to it, although in some places there are signs of glacial activity and other modifications by ice.

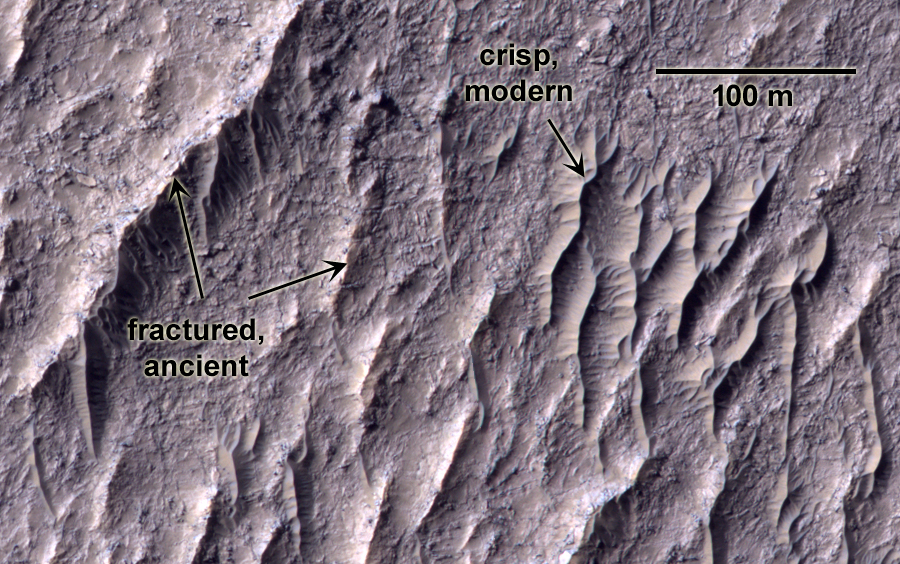

Here, though, what is interesting to me is the scattered windblown bedforms, like those in the scene below (yeah, I’m using the more generic and technical term bedform, because the Mars aeolian community hasn’t yet agreed on whether they are dunes, ripples, or something different that’s nearly unique to Mars, but rather they’re the more ambiguous transverse aeolian ridge, or TAR. Either way, you can think of a bedform as “fine-grained things blown and then piled up by the wind”).

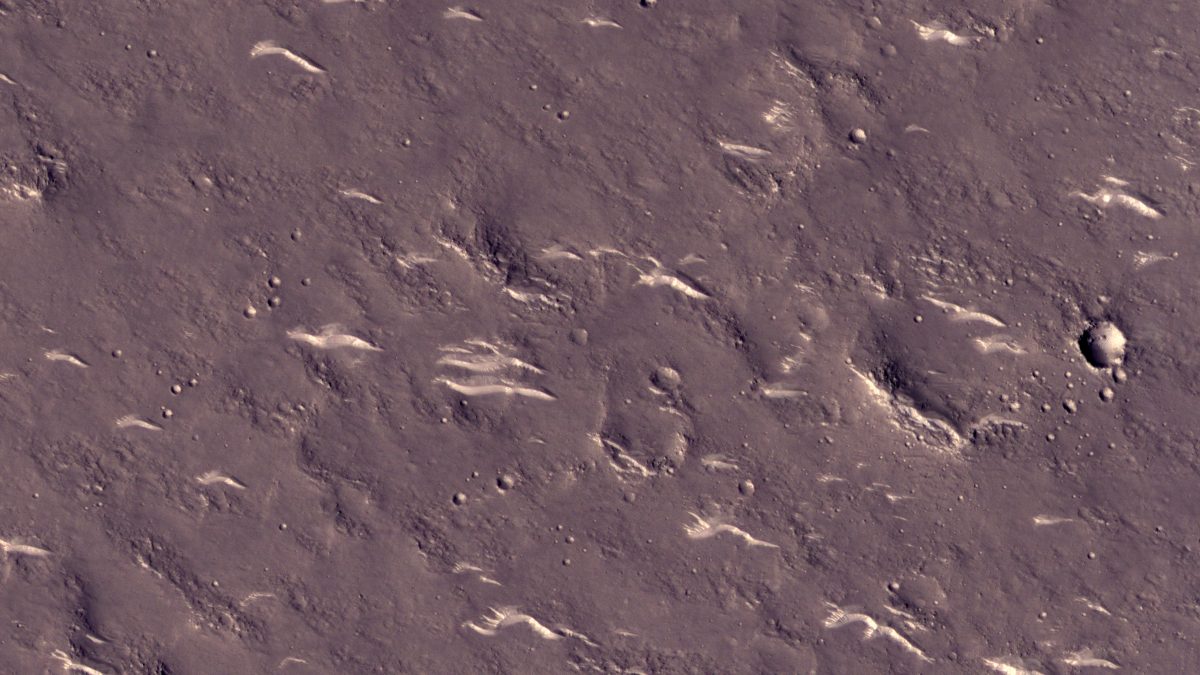

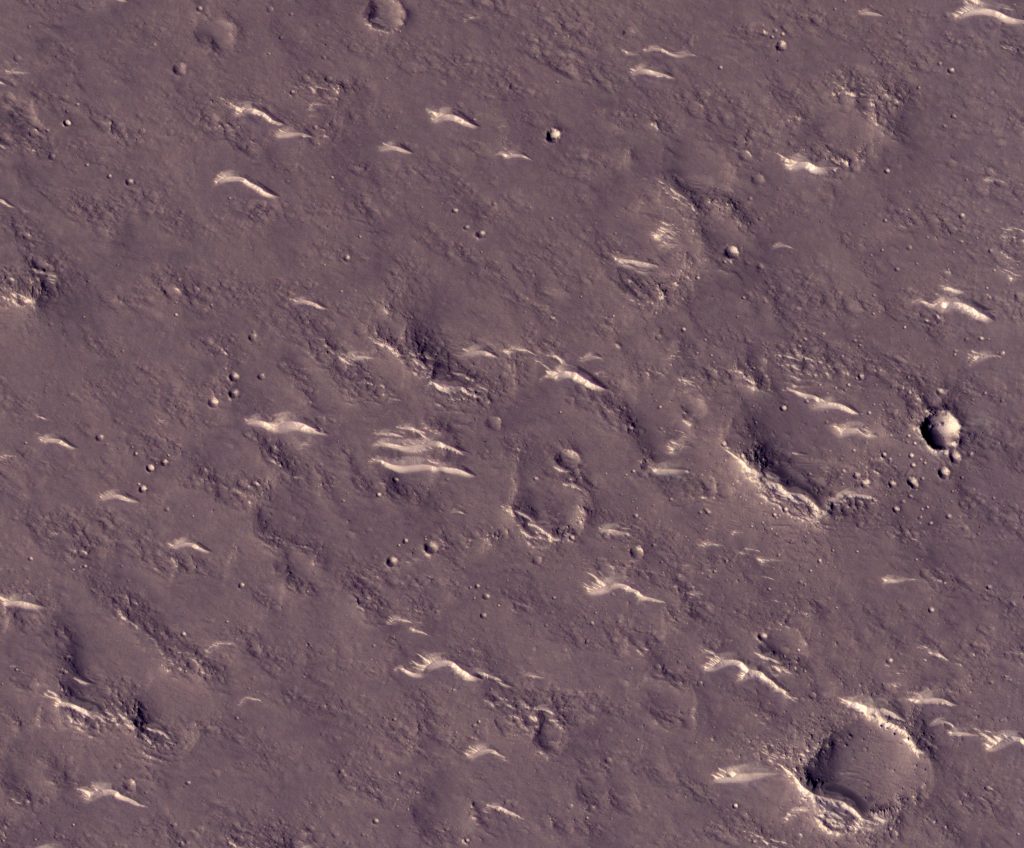

Cratered plains of Utopia Planitia, sprinkled with windblown bedforms. The view is 905×750 m (0.56×0.47 mi). HiRISE ESP_064467_2040. Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona.

The gray surface has a bunch of craters on it, most of which have become subdued over time, as they were eroded or buried by each others’ ejecta (craters spew up a bunch of stuff when they form and that makes messes that pile atop one another, like a bunch of rabbits digging holes in the same garden and letting their tailings overlap). At some point, not too long ago (but still maybe 1 billion years ago – that’s “not long ago” from a Mars geological standpoint) the wind formed the bright bedforms that are scattered across the scene. They tend to form either in local lows or along the old crater rims – it’s wherever sediment gets stuck as the wind tries to push it along. It’s a little hard to tell but I suspect the wind was blowing mainly from north to south (top to bottom) here.

Usually windblown things are the youngest geological features visible in a martian landscape. This is often true for Earth as well: loose sand erodes easily, so if you see them and there’s nothing on top of them, they’ve probably formed fairly recently. There’s one crater on the right side that’s younger than the bedforms, though. You can tell if you zoom in. This crater is ~35 m (115 ft) across. It’s still accompanied by some of the little secondary craters that formed with it, or perhaps the smaller craters next to it were made by smaller companions that flew in from space and impacted at the same time. I don’t know – but my colleagues who study impact craters could probably say more about it. It’s a recent enough event that you can still see some of the boulders that were flung out as the crater formed.

Notice that there aren’t any big bright bedforms on the rim of that new crater, like there are on the more subdued craters in the scene. Either that crater is young enough that they haven’t had time to form yet, or (more likely, I think), the period in which those bedforms piled up occurred – and then stopped – before that crater formed.

There is a pile of bright stuff inside the crater but it hasn’t formed into a nice big bedform (yet?). Instead that little pile of sediment has small ripples formed on it. There aren’t any such small ripples like this on the bright bedforms scattered around the landscape here – that suggests to me that they are probably somewhat cemented or indurated. That is, something has made most of the bright bedforms here cohesive and unable to easily respond to modern winds. That makes them relics that are part of Mars’ geological history.