The zebra dunes of the martian subarctic

Dune on a hill

September 2, 2020

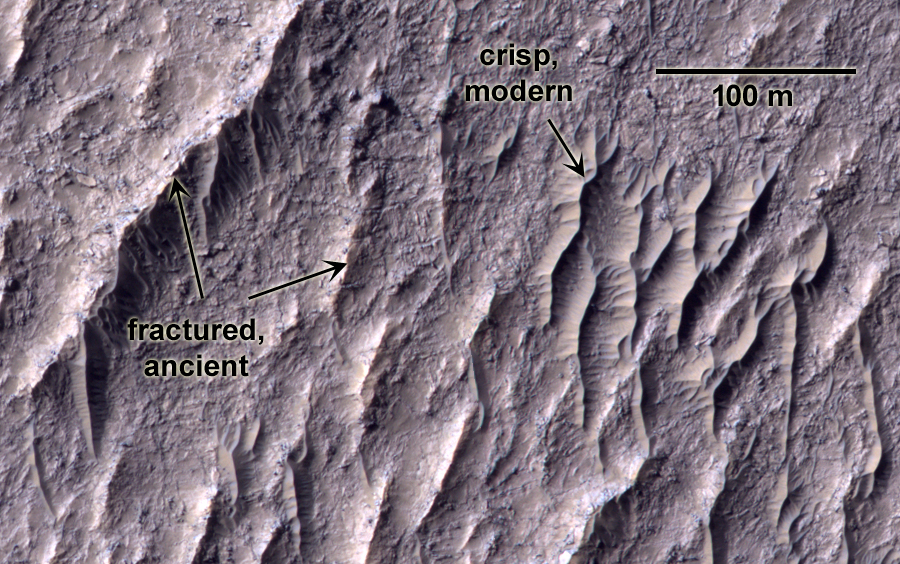

Both wind-carved *and* ancient

February 1, 202116 December, 2020

This year I haven’t had time to write many blog posts. That’s a shame, because they’re what often reminds me of how amazing Mars is (and by extension, the Earth, and all the other worlds out there). The pandemic has left its mark on all of us. I’m fortunate enough to be funded (but that may end – I don’t foresee spending on NASA to be plentiful in the coming hard years). The upside is that for now I can work. The downside is that I’m behind in all of my projects, and also trying to get my kids to do their schoolwork (such as it is this year).

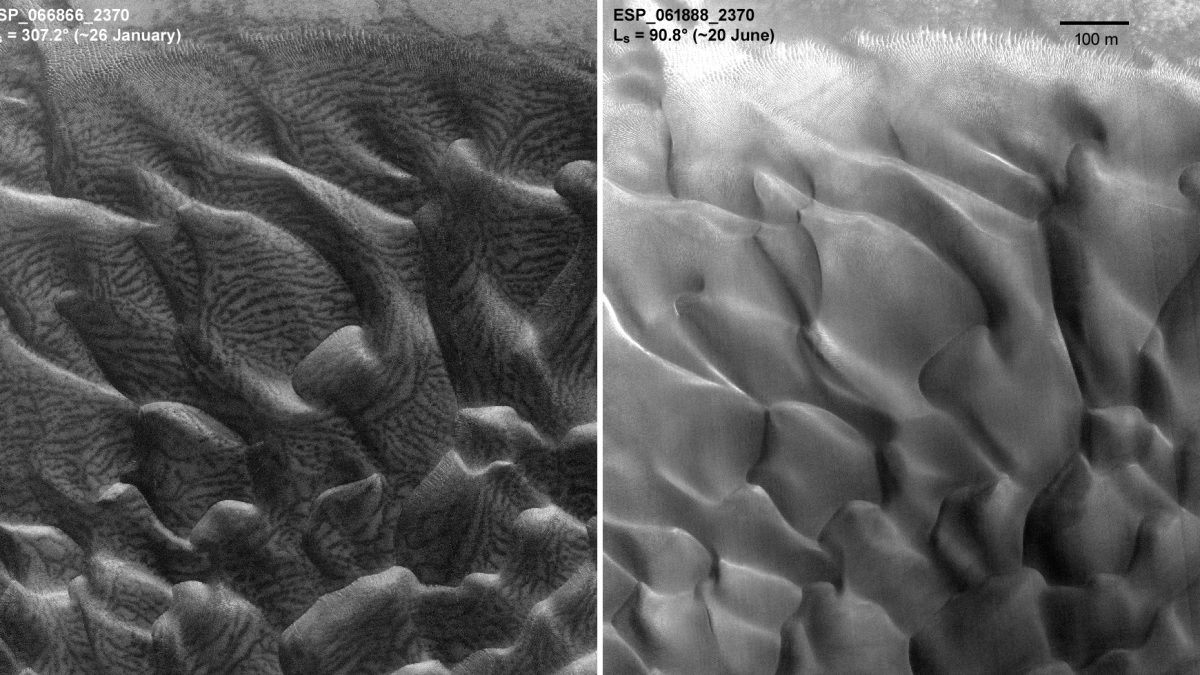

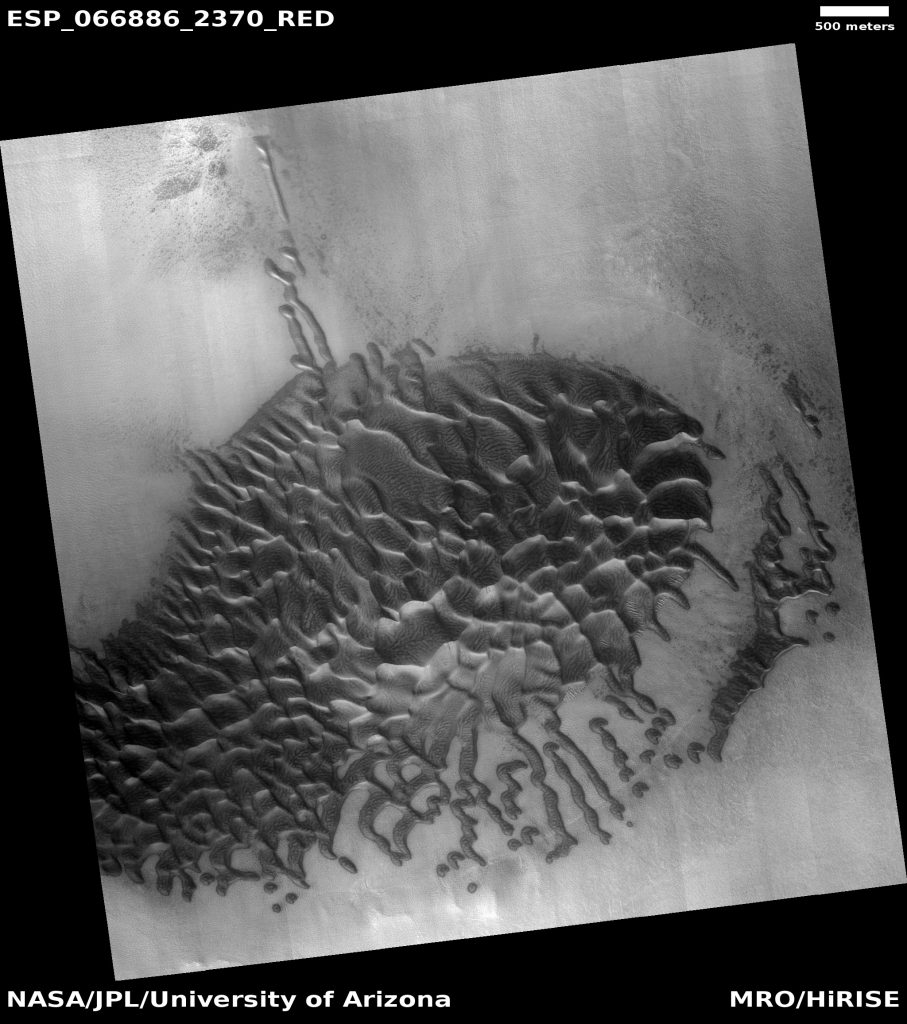

So let’s look at something cool on Mars. Let’s go see the zebra dunes. These zebra dunes:

Dunes aren’t typically covered in stripes like that. Not on Earth, and not on Mars (probably not on Venus or Titan or anywhere else, either, but so far we don’t have enough imagery to tell there). These dunes don’t seem out of the ordinary otherwise.

So what’s their deal?

The short answer is that I don’t know entirely. But I can get partway there by making some observations.

The first thing to realize is that this dune field sits at 56.7°N, which is in Mars’ subarctic. It’s not quite in the arctic circle, meaning it’s not far enough north to experience the midnight sun (in summer) or days without sunlight (in winter). But it is far enough north to be covered in wintertime CO2 frost, and to have very long nights and short days during the winter.

The second thing to note is that this image was obtained in midwinter, at Ls = 307.2° on the Mars calendar. The equivalent season on Earth would be about 26 January. There aren’t a whole lot of dunes in the Martian northern midlatitudes, so pictures like these are pretty scarce. There are plenty of dunes near the north pole, but at this time of year they’re experiencing days without sunlight, and so they’re incredibly difficult to image. In this particular image the sun is only 8° above the horizon (hold 4 fingers horizontally above the horizon and that’s about 8° – that’s a pretty low angle). So to summarize: images like this are rare, and they’re also a little weird because the sun is so low in the sky.

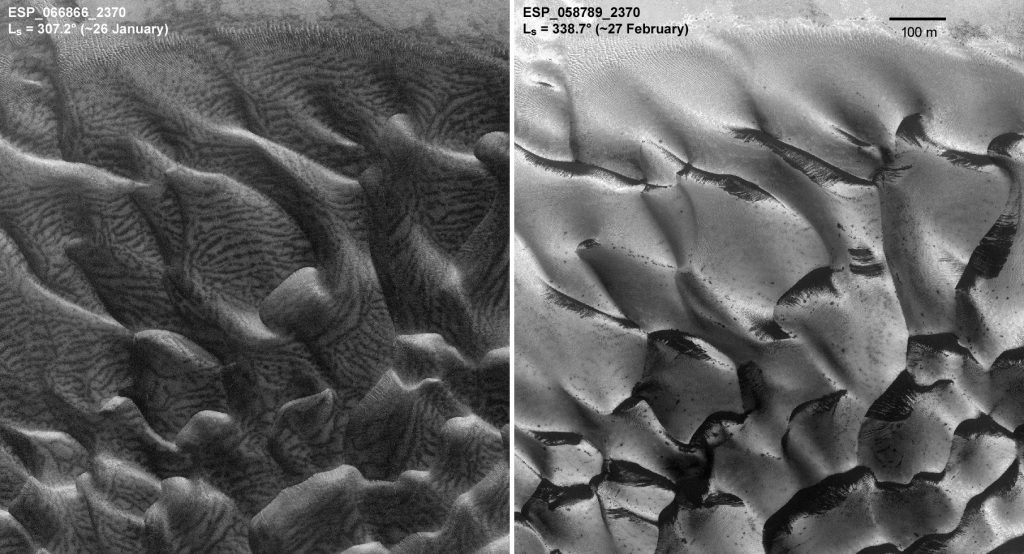

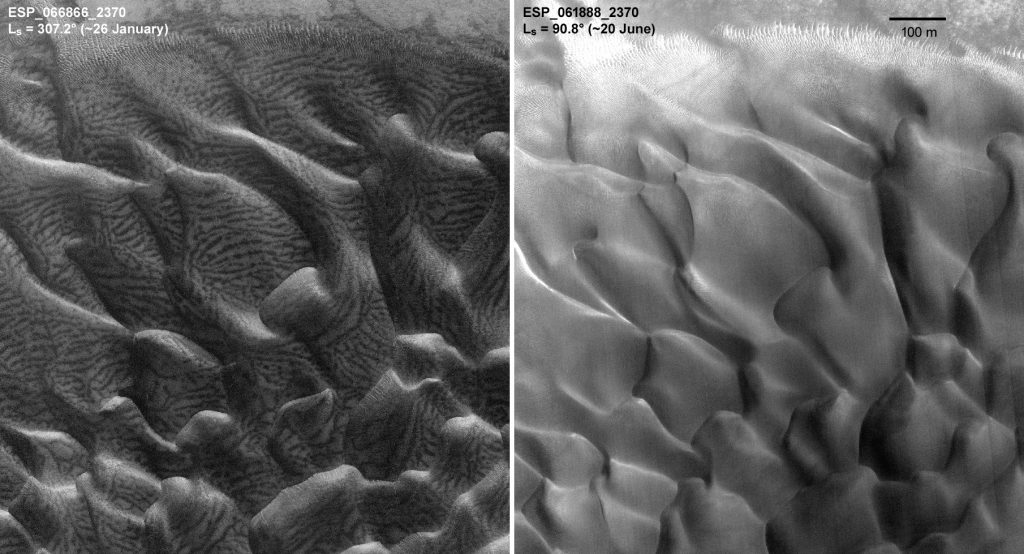

The third thing to do is to see if there are other images taken of this dune field. There are! And the stripes are not always there. Here’s a comparison of part of the winter image with a summer image of the same spot, when the sun was 45° above the horizon:

Winter on the left, summer on the right. The stripes only appear in winter. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

The winter image is covered in lots of frost. It’s dark because the sun is low in the sky, but if the sun were higher up then it would make that frost shine. For example, let’s compare the stripey winter image to one taken a bit later in the winter, almost at the beginning of spring:

In the late winter image, the sun has started to return to the northern hemisphere, and here it’s 21° above the horizon. The dunes are still covered in bright frost but the sunward slopes are beginning to defrost, revealing the true dune sand, which is very dark. There’s so much contrast in this image that in order to avoid overexposing the bright ice, the dark dune sand has been underexposed.

By late winter, the zebra stripes have begun to fade. This means the stripes are not part of the dunes at all, rather, they’re part of the seasonal ice. There are a lot of weird things that go on in CO2 ice (particularly, CO2 ice on top of dune sand) that we don’t fully understand yet. I have no quantifiable ideas just yet, but if you do, there might be a research project here.