Bask in Mars’ beauty, because you can

Dust Devil Fieldwork #5: Summary

July 11, 2019

Dunes or bacteria?

August 21, 2019August 5, 2019

It’s been a while since I posted anything. Not because I didn’t want to, but because I’m involved in so many projects that many things I love are being shoved aside for whatever has to be dealt with at any given moment.

It was a rough weekend and end of the week in the US – there have been a few quite prominent mass shootings. I’m not going to get political about it here. I’m just going to share my personal escape route from it all: gorgeous Mars. So. Here are a couple of scenes from Ius Chasma, one of Mars’ big valleys (it’s part of Valles Marineris – the word “Valles” is plural, since the area has a ton of huge cracks in it – Ius Chasma is one of the bigger ones).

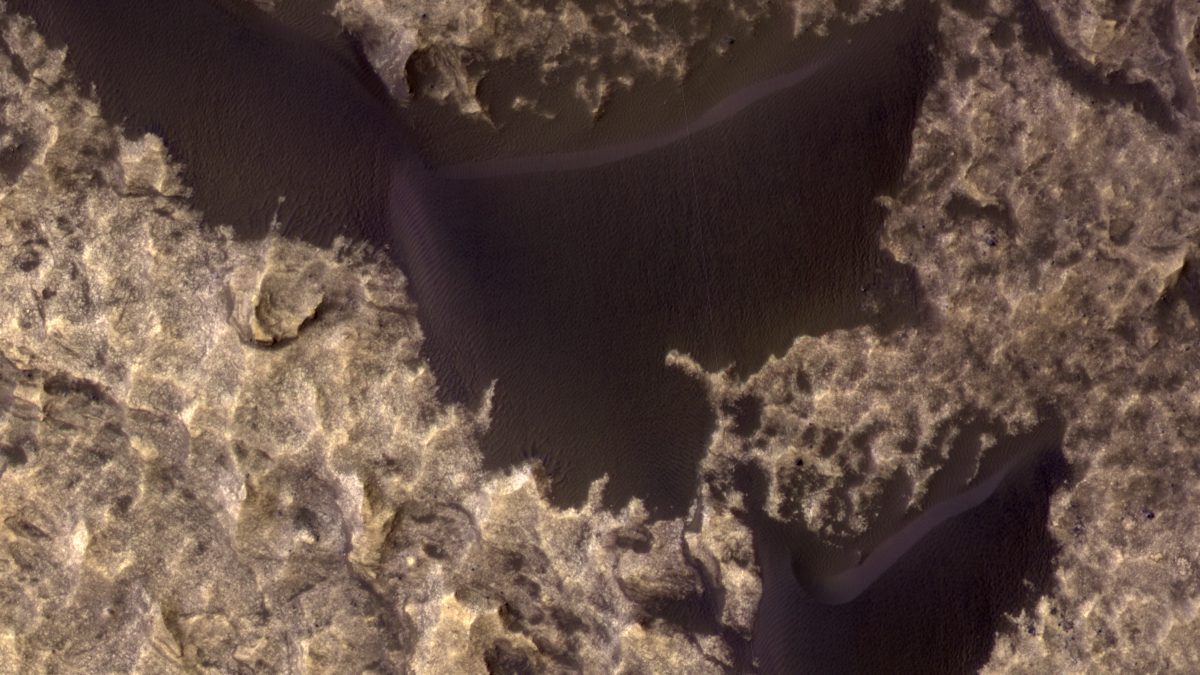

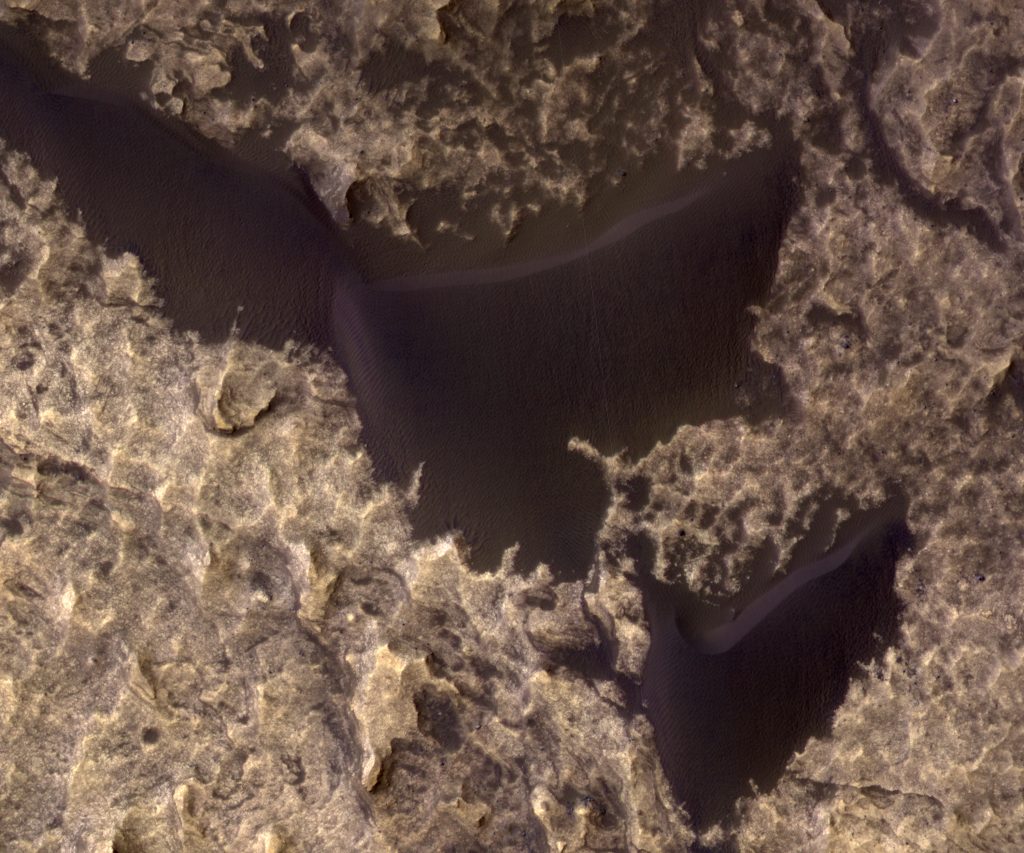

These frames come from this HiRISE image. If you follow that link and scroll down you’ll see where in Ius Chasma the image is located – it mostly crosses a ridge that splits Ius Chasma in half, lengthwise. The top part of the image is on the low, flat chasma floor. That’s a common place to find dark sand dunes, and indeed, this image has a couple of them:

Sand dunes in Ius Chasma on Mars, view is 750×625 m (0.47×0.39 mi). Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

What’s interesting is that these dunes have north-facing slip faces, so they’re migrating northward. Many dunes I’ve seen in the Valles are migrating southward, and in general most dunes at low latitudes (like these) are also migrating southward. But the Valles have a lot of topography that does odd things to the wind, so for whatever reason, here they’re going a different direction. It would be interesting to compare morphology, observed migration directions, and modeled wind directions. I’ve done that in a different valley (Ganges Chasma), and I can verify that, at least there, strong winds can blow in 3-4 wind directions over the course of a martian year (but northerly and easterly winds predominate).

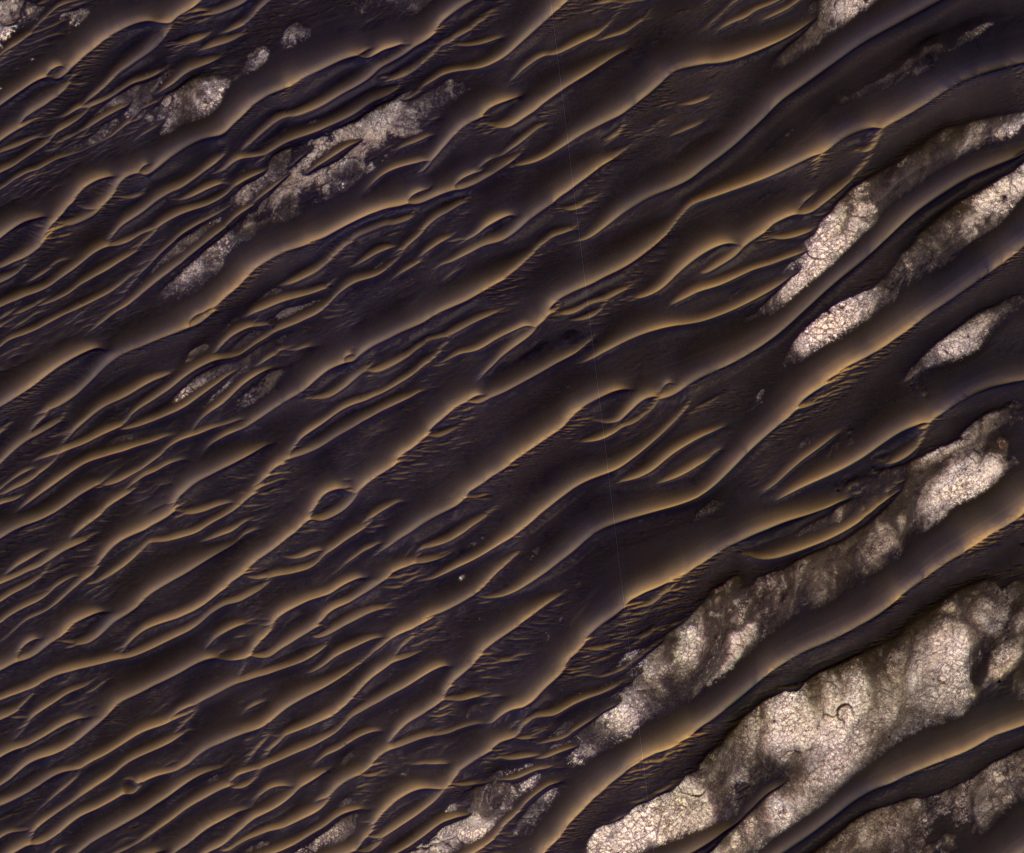

Farther up on the ridge bisecting Ius Chasma are some of these beauties, also known as TARs (transverse aeolian ridges). Shown at the same scale as the dunes above, you can tell that TARs are smaller than dunes. There’s no consensus yet on whether these are dunes or ripples or something new. But they sure are pretty. They seem to be made of grains that haven’t moved too far from where they first eroded, since very few have ever been observed to migrate (unlike the bigger dark dunes). They’re actually brighter than the dunes, too, but I’ve stretched the colors here to make them look nicer.

TARs in Ius Chasma on Mars, view is 750×625 m (0.47×0.39 mi). Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

The TAR beasties may be smaller but they are often longer than dunes. I like how some of these have unbroken crestlines, whereas other TARs have crestlines that have been reworked into smaller TARs that align to a slightly different direction. Does this record a change in prevailing wind directions? Maybe. A little downhill in this HiRISE image, the TAR pattern is much more regular, with crestlines that are less broken than these. Farther uphill, they’re even more broken up. It’s a good guess to presume the TARs first formed with unbroken crestlines and that something happened later on to rework them. But since we still know so little about what TARs are and how they respond to the wind and changes in sediment influx, it’s also possible that sometimes they just form looking as they do.

It’s a heckuv an image, and I recommend scrolling through it, if you need a break from your day.