Old dunes and new dunes

Why does Lori study dunes on Mars?

February 11, 2019

Dust Devil Fieldwork #1: Equipment

April 23, 2019On Earth, really old windblown dunes don’t usually survive long enough to become part of the geologic rock record. Dunes are made of unconsolidated sand, which is easily eroded by just about anything, so it takes special circumstances to keep dunes around. Most of the dunes preserved in Earth’s geological layers are just the bottom fraction of the dunes – the tops were cut off (quite often by other dunes!).

That same process has happened on Mars too. But in a few locations, something special has happened: entire dunes have been preserved. That must mean that the dunes formed and then were lithified quickly enough that they weren’t eroded away. More than that, they may have been buried at some point, like any other rock surface.

In a few locations, those dunes can be seen almost in their entirety. From orbit. It’s almost like looking at an aerial photo of a bit of Utah and seeing an entire T-rex skeleton poking out of the ground. As far as I know that’s never happened: usually finding fossils requires a lot of patience, training, and hard work on the ground. It’s not something you can find just by looking from afar, unless you get extremely lucky.

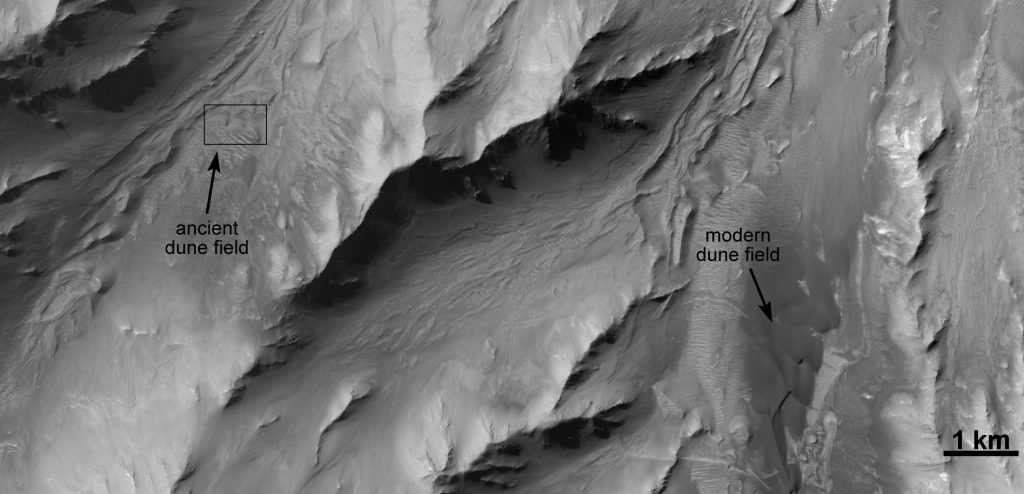

Here’s an example of one site I found while mapping modern dunes on Mars. I was looking through Coprates Chasma (one of the Valles Marineris). There are many small modern dune fields making their way up an interior wall of the valley:

Central Coprates Chasma: Map is THEMIS IR colorized by MOLA elevation, made in JMARS.

The black rectangle in the above image is shown below in more detail. In this image are both a modern dune field (on the right) and an ancient dune field (on the left). The ancient dune field is hard to identify, isn’t it? I’ve probably blipped past many of them in my search for modern dunes, but these were obvious enough that I noticed them.

Three ancient barchans, Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS, CTX image D18_034329_1661

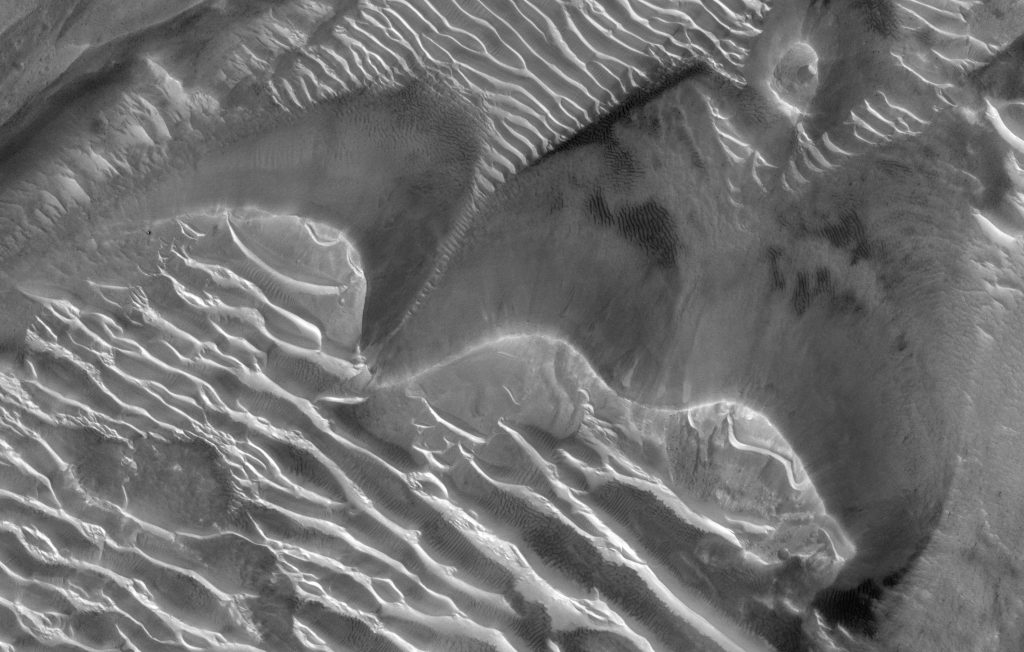

I asked for a HiRISE image of this old dune field to get a closer look (you too can request one with HiWISH!). Let’s have a look – here’s the bit covering the black rectangle in the previous image:

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona, HiRISE ESP_058698_1655

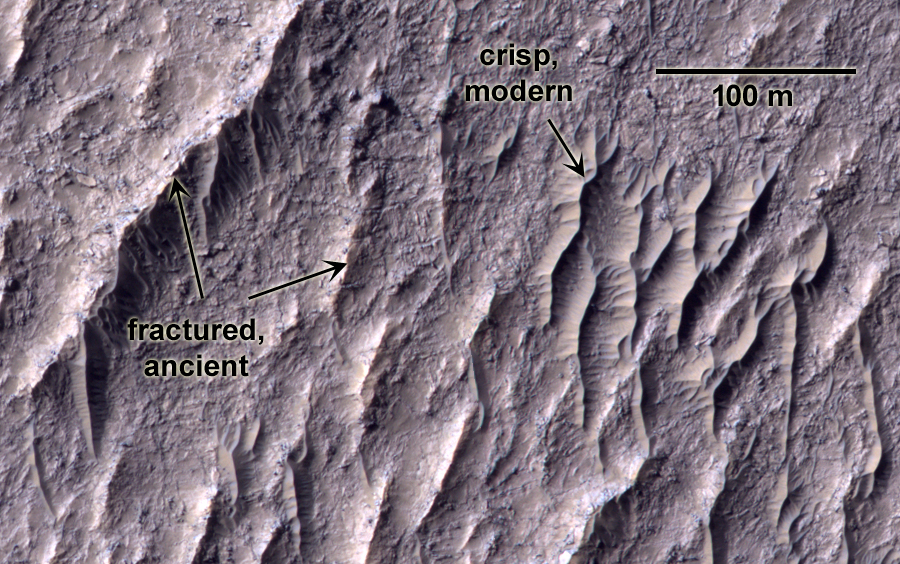

In the center of the above image are three remarkably well preserved crescent-shaped barchan dunes. They’re no longer active. Modern dunes are covered in ripples, but here those ripples have been buried or eroded away. Smaller brighter bedforms (that we call TARs) are migrating up (or maybe down, I can’t tell) the steeper slip faces — essentially they’re migrating over the old dunes as if the dunes were just another stationary hill to surmount.

There aren’t any craters on these old dunes. That could mean that they’re not so old, because they haven’t sat around long enough to be hit by anything falling from the sky. It’s also possible that they’re pretty old and were simply buried for a long time – that would also protect them from impacts. But I don’t see any evidence for burial (of course, that evidence could have been eroded away).

Another thing to note is that these ancient dunes were migrating uphill, toward the south. That’s the exact same direction that the modern dunes are migrating. That means that whenever those old dunes formed, the wind patterns were similar to those that blow today. That’s not too big of a surprise: winds from the north seem to predominate over many northern hemisphere and equatorial dune fields. It would be cool if we could date these old dunes, but that’s tough to do from just an image, especially one with no craters on it.

What a cool find!