Why does Lori study dunes on Mars?

Wind at the Mars InSight landing site

December 27, 2018

Old dunes and new dunes

March 4, 2019When I look for something to blog about, I usually go to the HiRISE catalog to see if there are any new pictures that I find interesting.

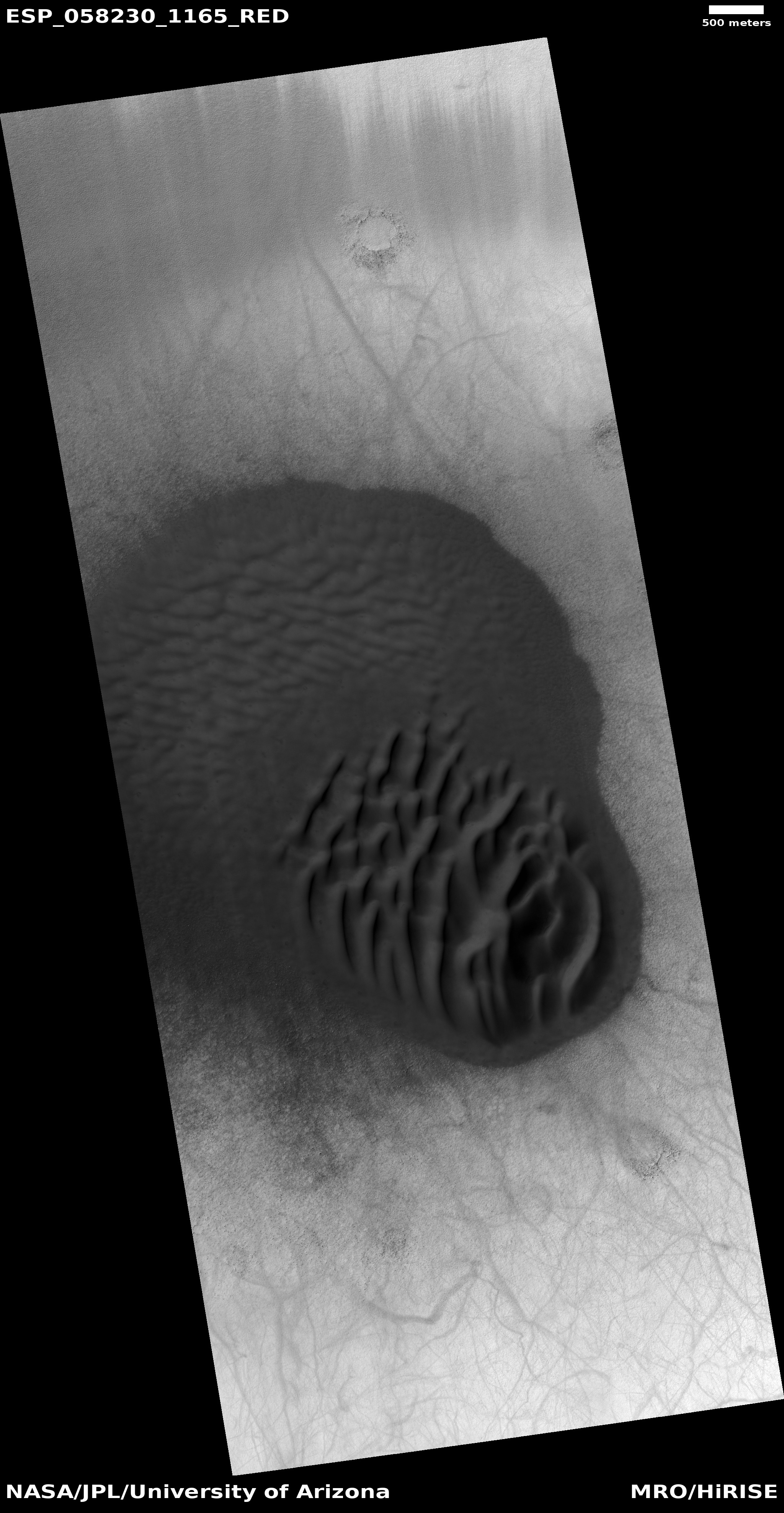

Today this lovely dune field caught my eye:

HiRISE images are about 6 km (3.7 mi) across, so that dune field is about 4 km (2.5 mi) wide and 7 km (4.3 mi) long. If you look carefully you’ll see that it’s a little bit weird. The entire dune field is surrounded by a crisp-edged area of sand that isn’t shaped into dunes (I call it an apron). That’s pretty unusual – compare it, for example, to the pretty little dune field in Noachis Terra that I blogged about a couple of months ago.

Why the difference?

Well the dune field I’m showing you today is located at a latitude of 63.2º S. That’s technically in the southern midlatitudes, but it’s edging towards being polar (for reference, the northernmost tip of Antarctica on Earth is at about this latitude). Something strange happens to dune fields at high southern latitudes. They get even stranger closer to the pole, but for today let’s focus on our high midlatitude dune field with its funky shapes.

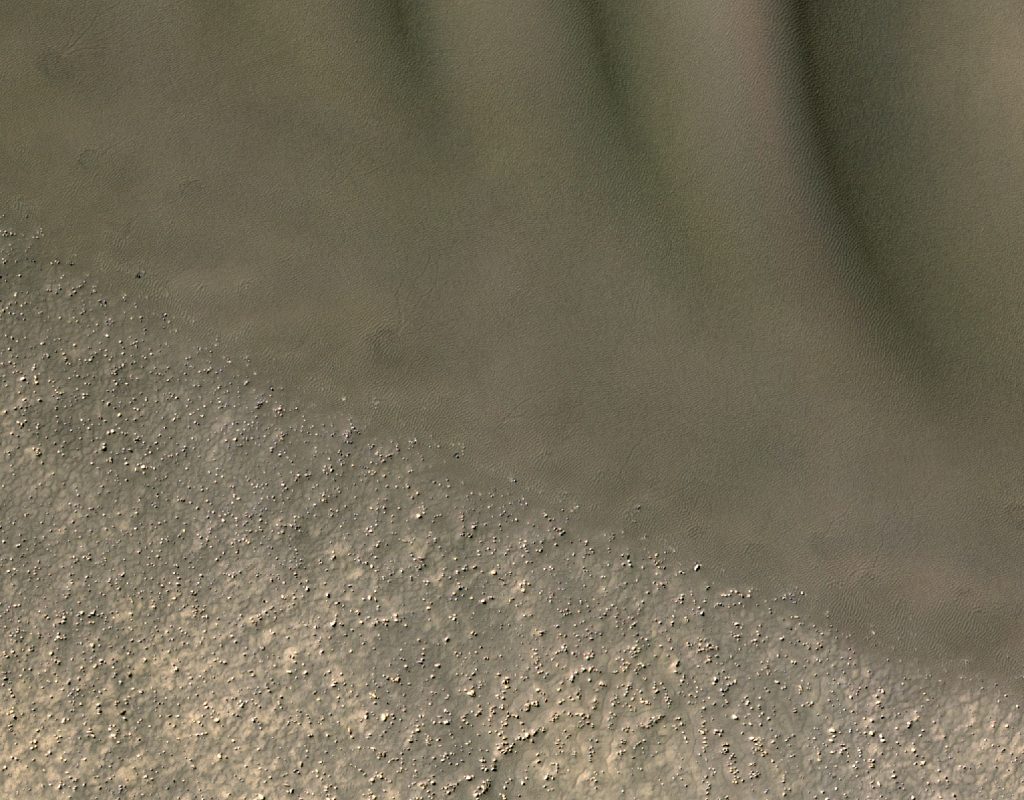

Let’s have a closer look at the apron:

Closeup of the lower (southern) edge of the dune field, view is 1.02×0.795 km (0.63×0.49 mi). (HiRISE ESP_058230_1165, NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona)

The apron looks a bit more diffuse up close, doesn’t it? At the top are the beginnings of the dune slopes. At the bottom you can see where a boulder-strewn field emerges from beneath the sand cover. If you look closely at the apron you’ll see some thin branching shapes that look almost like tiny rivers (they’re not rivers, it’s way too cold for water to flow here, and those are way too small anyway). Those things only form where the sand cover is relatively thin (you don’t see them much on tops of the dunes, for example), and folks have proposed that they’re formed every spring as winter frost sublimates. The proper term for them is araneiform (which means “spider shape” because they sort of look like spiders). You can find much nicer examples of them in other polar places on Mars, but I don’t think we’ve found anything like them on Earth (it’s not cold enough here, so the CO2 in our atmosphere doesn’t condense on the ground in the winter).

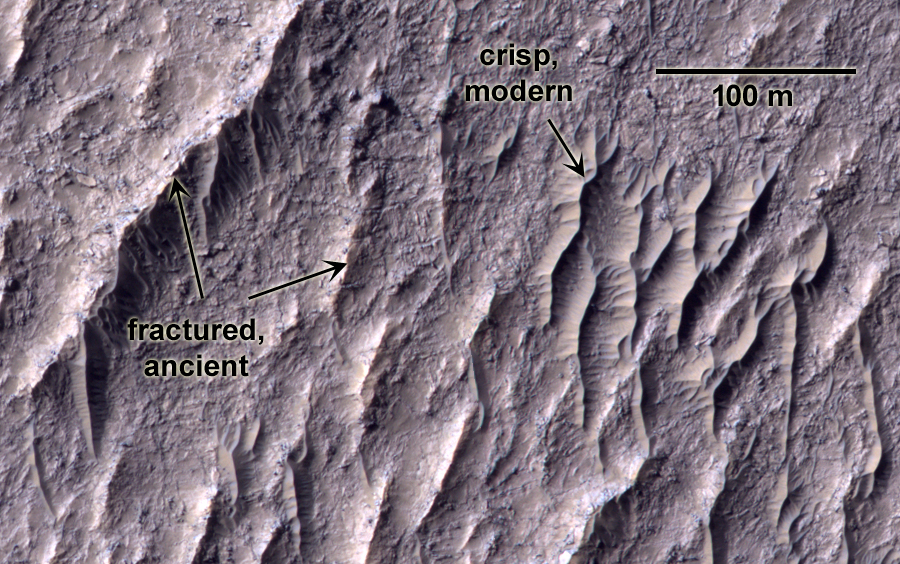

Let’s have a look at some of the dunes:

Closeup of some of the dunes, view is 0.65×0.5 km (0.40×0.31 mi). (HiRISE ESP_058230_1165, NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona)

These don’t have the crisp brinks like dunes found at lower latitudes. And they do have little ripples all over, but they seem a bit disorganized, not like ripples on dunes at lower latitudes.

Why are these high latitude dunes so weird?

Back in 2010 I wrote a paper with Rose Hayward of the USGS, proposing that the dunes look softer and weirder because they’re not as active as lower-latitude dunes (that is, the wind doesn’t reshape them as fast). We proposed that high-latitude ground ice was locking the dunes in place, keeping the wind from refreshing their shape.

In 2018 a group of us led by Maria Banks of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center actually measured the migration rates of dunes and ripples in the southern midlatitudes. We found that the higher latitude dune fields are in fact less active than those at lower latitudes. Score one point for measurements matching up with inferences from morphology! *cheers*🙌🏼

Ice in the ground fills the spaces between sand grains, acting like glue to stop the wind from moving the sand around. There isn’t much ice at lower latitudes, so it doesn’t affect the dunes and ripples there.

The fact that high southern latitude dunes are slower and seem more eroded could be caused by at least two different things:

1. (Less interesting) Dunes and ripples are forming and moving at high southern latitudes, but because of the ground ice, they do so more slowly than dunes at lower latitudes. They’re born that way, baby. (On second thought, that’s still interesting, because it means high latitude dunes would then record wind patterns over a longer time period than low latitude dunes. But they’d be hard to interpret.)

2. (More exciting) Dunes and ripples in the high southern latitudes formed long ago, in a climate state where the ground ice wasn’t yet formed, and have since become mostly locked in place. We’re essentially looking at fossil dunes. That means their shape would record ancient wind patterns, which we could compare with modern winds to see how the climate state on Mars has changed. It means we could use dunes to study climate change on Mars.

We still don’t know which of the two it is (or possibly both?). But if I figure out more, I will blog about it. And there will surely be pretty pictures to go with it, as always.