Where is the Roman Watch Tower?

Stellar Death

December 22, 2009

The road to scientific advance

January 8, 2010It is almost time to leave for Xmas vacations. Finishing up a few things and getting ready to leave to Italy. There are many aspects that make these holidays appealing. Among those, is an archaeological exploration foreseen for the first sunny day between X-mas and new year’s eve. This story begins a couple of years ago, when I studied the orientation of the ancient church of St. Peter above Zuglio (the Roman town Julium Carnicum). While reading the related literature I realized that, at the times of Romans, this and other similar sites (all on mountain tops), were used as sight stations, to visually communicate the arrival of possible invaders (by means of smoke in daytime and fire during the night) to the large town of Aquileia. This town had been founded in 181 b.C. to prevent the invasions by barbaric tribes from the NE of the Italic peninsula (ad Illyricos objecta montes), which has a rather easy to cross border. One of the possible ways to trespass the Roman limes was a narrow pass, today known as Plockenpass. But from there all the way to Aquileia (about 80 km to the south, on the Adriatic sea) the landscape is full of mountains and it requires a number of intermediate stations before one finally reaches the Friulian plain.

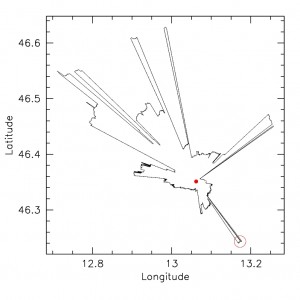

My curiosity was captured by the fact that while it was clear how the visual signals would get along the valley from Plockenpass down to what today is called Cesclans (known archaeological site on a high, easily defensible top), much less clear was how those signals could get to the plain. In fact, a chain of mountains prevents the sight of the Friulian plain from Cesclans. Clearly, a further station was required. I took a note and let the thing rest for quite some time. But at some point, I realized that I could use the SRTM survey data for my archaeoastronomical studies. While doing this I also thought that they might be of some help to solving the problem of the missing station remotely, even before thinking about an on site expedition (it is about 500 km from here, just across the Austrian/Italian Alps). The idea is simple. You write a program that, using the digital elevation data provided by the Shuttle Mission (and free for download), determines the distance of the horizon in all directions seen from a given site (taking into account Earth’s curvature and atmospheric refraction). I had originally done this to produce synthetic horizon profiles for the analysis of some proto-historical sites in the Friulian Plane. But the application to the case of Cesclans was straightforward. You can see the result in the graph here to to right. The red dot marks the position of Cesclans. As you can see, there are several windows that open the sighting to NE and NW (the rightmost is the one which connects to the Plockenpass valley), while to the south the horizon is closed. With one, narrow exception (marked with the red circle).

If you go to a map, you will see that this coincides with a 750m mountain in the pre-Alps. This is Mount Faet, by coincidence (!) just above my small town of Artegna. Immediately after finding this result I wrote to a friend of mine that lives in the area, asking him to verify whether this window was real and not just an artifact of my calculations. The day after I received a digital picture taken with a tele-lens from Cesclans in the appropriate direction. And, indeed, a tiny portion of mount Faet was visible (if you knew it was there).

The next step was to go on site, with the aid of a GPS, to see whether in the relevant area (my calculations were giving a spot with a diameter of roughly a km, at an altitude between 550 and 600m above sea level) there was any trace of human artifacts that could indicate the possible presence of statio. Nice plan for summer vacations.

So, at the end of August, with my young assistant Riccardo, I left my place and started hiking along an ancient path that leaves from the base of the mountain. Interestingly, there is a network of stone paved paths that lead to the mountain top, which have been attributed by archaeologists to post-roman epochs. According to them, the mountain was used a refuge during the barbaric invasions that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. We started off very early, in the fresh air of dawn break. The GPS was telling me that it would take about one hour to reach the site, although the straight line distance from the starting point (placed at about 300m above sea level) was less than two km. I knew that path, since I had been there many time during my childhood to collect chestnuts. But I had never paid so much attention to the way the path was paved. Indeed, it is kilometers of stones. At times, in between the threes, we could see flat embankments surrounded by stone walls, probable relics of those ancient refuges identified by the archaeologists. From time to time, we get a glance of the Friulian plane that extends to the south. At some point, a message appears on the GPS, telling us that we are within 50 meters from the targeted position.

By coincidence, there is a clearing in the wood produced by a track recently built to facilitate the access to the mountain (to prevent fires and so on). From there, we can finally look into the direction of Cesclans. And indeed, there it is. We can see the mighty tower of Cesclans’ church with naked eye in the light of the rising sun, just above the low mountain. You can easily see it if you click on the photo here to the right.

This is the definite proof that there is a sight-line between the two sites. Notably, from mt. Faet you can see down the whole Friulian Plain and, in clear days, you can even see the sea. Obviously, Aquileia is still far, but the Plain has several hills that could be easily used as intermediate stations. So, this is not much of a problem. However, having a viable sight-line is one thing. Being certain it was used by Romans as part of their defensive signaling system is a different issue, which can only be demonstrated by archaeological findings.

For the time being this remains an interesting possibility, supported by visible, ancient human manufacts. That day, Riccardo and I adventured a bit in the bushes and found several traces of stone walls close to the sighting site. At home, then, I had a look into a book describing an archaeological surfaces survey carried out in the early eighties in this part of mt. Faet. Indeed, these manufacts were classified as defensive structures dating back to the Longobard period, possibly built on Roman relics. All of this makes the thing even more appealing. In the same publication I also found the description of a number of proto-historical mounds, not far from the site Riccardo and I visited last August. That is the target of the visit planned for the X-mas holidays. This has now brought me rather far from astronomy (from which I started), but it is extremely stimulating and helps me getting back from void spaces into humanities. Although far into the past…