Historical wind and modern wind

Once covered, now revealed

March 29, 2021May 3, 2022

I don’t typically have much time for these posts anymore. The pandemic seems to have changed everything. But sometimes I need to remind myself why I do this for a living. Going to look through Mars’ gorgeous scenery is one way I can ground myself (pun not intended). My hope is that by writing these blog posts, I can perhaps share some of that with others.

So let’s have another awesome look at Mars, hmm?

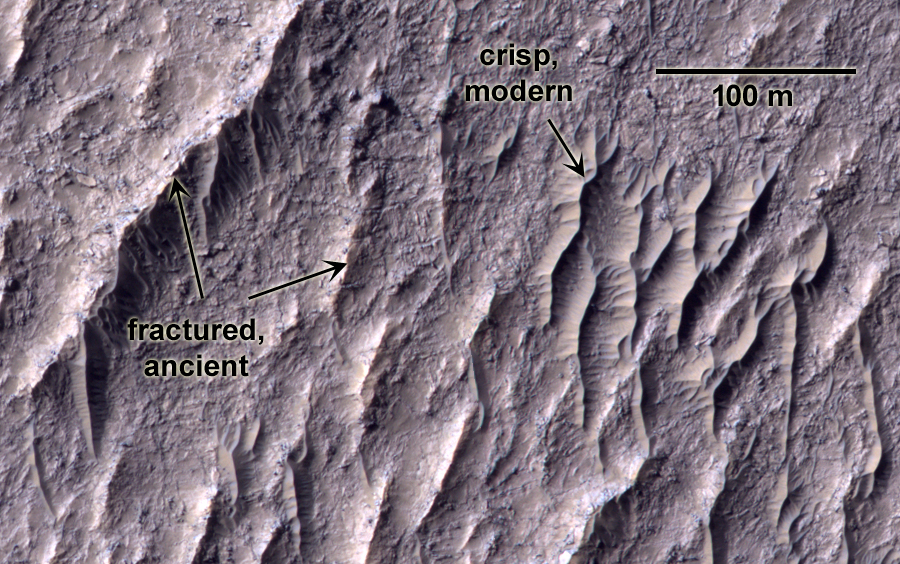

HiRISE image ESP_069655_1510. Most of the topography is either old, eroded windblown dune-like features, or modern ones that are quite similar. View is 920×575 m (0.57 x 0.36 mi). Image credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona.

Go ahead, click on it so you can see it at full resolution.

There’s a fabric of hills going from the lower left to the upper right. If you look carefully you’ll see that some of them are gray, fractured and rubbly and others are sharp-crested and brownish:

This particular site is located in the ancient cratered plains on Mars known as the “southern highlands“. Specifically, this is in Noachis Terra (or Noachis Terra by Bernard L’hoir, if you’d like a sweet musical backdrop while you’re reading this). There are a lot of surfaces between the big old craters that look a lot like this: broken and battered, eroded, and scattered with more modern windblown dune-like features. They’ve been dated to at least 3.7 billion years old, so we’re looking at terrain that’s been sitting around for a very very long time.

(Note that by “modern” I mean it they have no superposed craters and they look fairly crisp at this scale, so they may be anywhere between hundreds of years old to a few hundred million years old. Mars does not do fast fashion.)

(Note also that I’m carefully calling them windblown “features” because they’re not really ripples or dunes, but a (perhaps uniquely) Martian feature called a TAR.)

The older, beaten-up hills are probably ancient versions of the more modern wind features. Have they been sitting around like that for more than 3.7 billion years? Maybe, but I’m guessing not since there aren’t any craters in this image at all. These rocks were formed ages and ages ago, but since then the surface has undergone erosion – enough to erase any small craters that surely would have peppered the surface in the intervening time.

Some scientists are looking into these eroded surfaces, trying to figure out if their erosional patterns may provide clues to how they formed in the first place (e.g., Cowart et al., 2019). It turns out it’s hard to figure out how rocks formed when they’re billions of years old and all you’ve got to go on is a nice view from orbit and some thermal data that might tell you something about the rock’s composition and competence. Lots of different rock-forming processes can lead to similar-appearing surfaces. We’d have to send a lander or rover (or a geologist!) to know for sure.

What I can tell you, though, is that at some point these things happened:

1. The surface formed, somehow. Maybe it was a lava flow, or a volcanic ash deposit, or a windblown expanse of sand, or a huge glacial deposit, or a lake floor, or maybe it was any of those that was then pulverized repeatedly by impact craters. All we know is that it was a very long time ago. Otherwise, we don’t know.

2. At some point the surface was eroded, probably mostly by wind. The old hills there might be the last gasp of wind-formed features that stabilized and lithified.

3. Maybe it was buried at some point by dust or sand. This would have protected the current surface from cratering, perhaps explaining in part why there aren’t any visible craters. It might also explain how the wind-formed features became lithified. Then again, maybe it wasn’t buried. We don’t know. But if this happened, then all that stuff was then eroded away again.

4. The “modern” windblown features formed, angled slightly differently from the old ones (indicating they were built by slightly different wind circulation pattern – yes, Mars has weather and climate change too!). I like how some of them have used the old ones as anchor points to grow on, kind of the way some species of trees like to grow out of stumps of fallen trees.

Anyway, this has been my recent cathartic spewing about Mars and its wind. I hope it does you some good too. Thanks for reading!