A long concealed book

The Crime of Galileo

November 18, 2009

Galilean Nights @ Home

November 23, 2009I occupy my free time doing very different things. One of them is archaeoastronomy. There will be a post on this topic, which I found quite intriguing (meanwhile you can find some more info here). One of the most common (and easiest) studies in archeoastronomy (although in this case the term archaeo is probably not really appropriate) is about the orientation of old churches. While reading the available literature on this subject, I found a recent, very well written and informative book, The Sun in the Church – Cathedrals as Solar Observatories, by J.L. Heilbron. At some point, in the chapter The Accommodation of Copernicus, under the section Book Banning, subsection Galilaeus Sanctificatus (!), I found a very interesting piece of information (pp.210-211). Here follow the relevant excerpts.

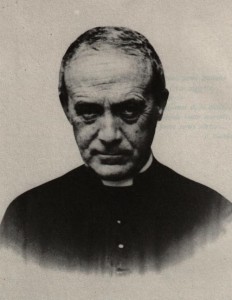

“The removal of Galileo’s Dialogo from the Index canceled a black mark against the book but not against its author. The official rehabilitation of Galileo took another century and a half. It began around 1940 in connection with the three hundredth anniversary of Galileo’s death. That was not a good time for a party. Nevertheless Pope Pius XII approved a campaign to demonstrate the Church’s openness to science. As an indication of this openness and on the recommendation of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, he commissioned an unrestricted biography of Galileo. The assignment went to Monsignore Pio Paschini, rector of the Pontifical Lateran University, a historian known for his balanced account of the Church during the Reformation.”

My surprise was two-fold. First of all I was not aware that the Pope had commissioned such a work (this already tells you the level of diffusion this book had. But wait…). Secondly, Pio Paschini (1878-1962) was born in Tolmezzo, some 25 km from my village in Friuli (Italy). He had actually written a very extensive History of Friuli, which I knew rather well.

That I had to learn about this in a book written by a Berkely professor was astonishing in itself. But my wonder was going to grow even larger in the next lines.

“It was a bold choice, since Paschini tended to be liberal and judicious. These virtues worried some of the Pope’s senior advisors, who had the satisfaction of being proved right. Paschini took Galileo’s part, admitted that the condemnation had been an error, and lost no opportunity for criticizing the Jesuits, on whom he blamed the entire affair. The Jesuits objected. Paschini’s two-volume work disappeared in the review mechanism, much as academic articles submitted to scholarly journals do today. The anniversary date, 1942, was long past when the Vatican journal, Civilta’ Cattolica, got around to the subject. It admitted that the Church, or rather, intemperate and ill-informed churchmen, had erred in condemning Galileo; and it recommended that the best use that could be made of this fact was to forget it. Paschini understood and fell silent. As a reward he was made a bishop two months before he died and an honorary member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, which had opposed the publication of his work.” With this unimaginative solution, the Church shut up a work that it had commissioned to demonstrate its openness.”

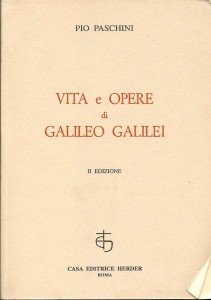

The book had to wait. The third centenary of Galileo’s birth (1564) was just missed and the book appeared after its author’s death.

“Paschini’s biography of Galileo appeared in 1968, heralded as an indication of the Pope’s program for the peaceful coexistence of religion and science. The general scholarly press reviewed the book favorably. Lay and clerical critics commended its balance. Very few knew that, to use an old expression of the censorship, the book had in effect been indexed ‘donec corrigatur’, and then corrected before publication, by the keeper of the Jesuit’s archives. Since the publication of this collaborative work, efforts at rapprochement between science and religion have intensified, particularly under the auspices of John Paul II. In 1979, on the occasion of the centenary of Einstein’s birth, the Pope told is Pontifical Academy of Sciences that he wanted theologians, scientists, and historians to work together on a reassessment of the Galileo affair. He endorsed Galileo’s principles of biblical exegesis. He gave as an earnest of the project Church’s sponsorship of Paschini’s biography, without knowing (let us hope) that it had been censored more crudely than the old books on heliocentric astronomy.”

The edition I managed to get dates 1965, so I am not sure where Heilbron got his 1968. But it does not make very much difference. The book had been concealed for more than 20 years and his author never received the appraisal he deserved. Also, for some reason, it did not get very much diffusion outside of scholar circles. You can find some mention to it here.

At the time I was reading The Sun in the Church, a new 0.7m telescope was about to see his first light on the Friulian alps, a few km north of Tolmezzo, were Pio Paschini was born. I was acting as a scientific consultant for the amateur association that manages the site, called La Polse di Cougnes. I thought that in consideration of all his objective work on Galileo (although certainly supported by his submissive Friulian spirit, for Paschini the whole business must have been a hard knot to swallow), and in sight of the IYA2009, dedicating the telescope to his memory in his own land was the least we could to. I proposed this to the coordinator of the association, who accepted this immediately. And so, on September 27th, 2008, the telescope was solemnly dedicated to him. Since then hundreds of visitors enjoy the sight of the celestial wonders.

Hopefully, in the future his work will be properly recognized and the Church will take all necessary steps to give proper credit to his commitment for an objective evaluation of the Galileo affair.