Our Predictions about Pluto: Getting it Right/Getting it Wrong

The Slumbering Dwarf Awakens: Pluto is about to come back into the limelight

September 3, 2015

The Three Discoveries of Pan

March 9, 2017

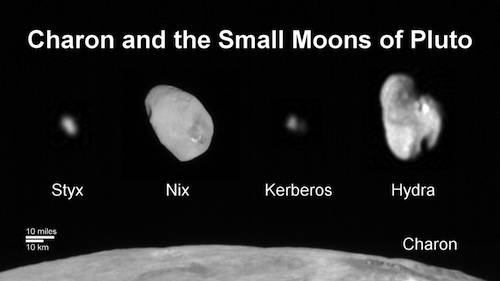

Family portrait of Pluto’s four small moons

Back in June, my research colleage Doug Hamilton and I put out a paper in Nature magazine about the four small moons of Pluto. The timing was not accidental. Although the paper was the culmination of years of work with the Hubble Telescope, we knew that a lot of our predictions would be tested barely a month later, when the New Horizons spacecraft passed Pluto. Making predictions that might be proven wrong is part of the fun, and also part of the danger, of scientific research.

As we all know, the flyby was a great success and we are now waiting, patiently, for the slow trickle of images and other data to come back from the spacecraft. Today, NASA has released the first “family portrait” of Pluto’s four small moons. As someone who has spent years studying these objects as nothing but faint dots, I find it is enormously gratifying to see them as resolved bodies, with shapes, colors and surface features.

So what did we get right? Well, based on years of studying how the brightness of each body varies, we were able to determine the rough shapes of the two larger moons, Nix and Hydra. On that point, we nailed it! Also, by making assumptions about how bright the surfaces are, we could make estimates of their sizes. We have learned that the moons are a bit brighter than we expected, and therefore a bit smaller, but overall our predictions have held up well.

…with one big exception–Kerberos. Our paper predicted that Kerberos would be big and dark, whereas the image clearly shows an object that is small and bright. What went wrong? Well, it all comes down to the moons’ masses—how much they would weigh if you could put them on a scale. The only way to determine the masses of these moons is to study how each one subtly alters the courses of the others. Based on years of precise measurements, our colleagues believed that they had weighed Kerberos, and its mass was surprisingly high–about a third that of Nix and Hydra. On the other hand, from our measurements, it only reflected about 5% as much sunlight. The only way to make an object that faint and that massive is to make it very very dark. That darkness, comparable to that of a charcoal briquette, is not out of line with other bodies in the outer Solar System, but it certainly made it different from its Plutonian siblings.

We know now that Kerberos is small and bright. If the mass determination is right, then Kerberos is absurdly dense–many times denser than lead. That seems unlikely. We therefore conclude that we probably had a broken scale. Because weighing the moons of Pluto is such a tough job, this is not out of the question. Now that we have new and more precise measurements of the orbits of the moons, I boldly predict that we will soon learn that the mass of Kerberos is much lower than we had previously thought.

One word of caution, however: my bold predictions don’t always turn out to be right.