Dust Devil Fieldwork #5: Summary

Dust Devil Fieldwork #4: Team Paparazzi

June 16, 2019

Bask in Mars’ beauty, because you can

August 5, 2019July 11, 2019

This is Part 5 of a series on my dust devil fieldwork in 2019 (see Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4).

We came back home a couple of weeks ago. I’d say our field campaign was a great success, considering how much data we collected. I’ve started sorting through it and it’s going to take me a while to start making sense of it. I want to give a shout out to our undergraduate students from St. Lawrence University, Banner Cole and Owen Sprau, and to our graduate student from UCLA, Taylor Dorn. There’s no way we could have accomplished all we did without their help, and I’m grateful they were there.

I am of course also grateful to have had awesome help from my colleagues Steve Metzger and Stephen Scheidt, who know way more about cameras and meteorology instruments than I do, and to Tim Michaels (our remote meteorologist, the mysterious voice in the phone). I’m lucky to have had a great team, and it’s because of them that we have awesome data (and also some good stories). Here’s a picture of us at the met tower, with one of the SETI Institute Expedition Flags.

I’ve already shown some pictures of dust devils in previous posts. We saw plenty of them, but we also saw much more than that. There were thunderstorms on many days, most of which didn’t produce any rain (at least not on our playa). But many of them created haboobs that sometimes inundated our camp with a dust storm – sometimes several of them passed through in succession. One of our first days there we got hit by a strong haboob, leaving us scurrying to cover up our food and reinforce tent stakes. That day, the wind blew hard enough to mobilize the loose sediment and form little ripples.

One day one of these storms blew for 40 minutes, so we sat in our trucks and waited it out. Seriously, dust for 40 minutes straight. After a while I set up my phone to take images of the same bush, about 20 feet away. There were times when I couldn’t see the bush.

The scenery in Nevada makes for a really incredible backdrop for the instruments:

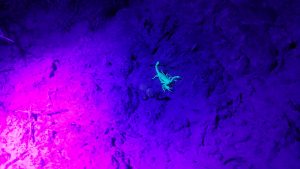

It turns out that scorpions glow in UV, which makes them ridiculously easy to find at night if you have a UV flashlight. Which we did. One night the six of us spent a good half hour trolling around the bushes and rocks near the camp, looking at scorpions and rocks that fluoresce.

It was also a great place for astronomy. We were there long enough to observe most of a lunar cycle, and Jupiter was a lovely sight in the evening.

We also took breaks from the work, letting the instruments collect data while we investigated the area. One day we drove up the nearby mountains into a park. Unfortunately the snow wasn’t entirely melted, so the streams were still quite active, which sometimes made for wet roads. To get your truck out when it is stuck in the mud, I recommend always bringing along shovels and undergrads. They can work wonders. And then go relax and have some blue tea.

I have so many more pictures and memories than I can share here. In the coming months I’ll make sense of our data and start figuring out what we can learn from it. Stay tuned, as I’ll probably write more posts about it once I’ve got something coherent to say. And next summer we’ll go and do it again, maybe at the same site.