Where dunes once trod

Oh, Mars!

August 2, 2018

Different sands

August 21, 2018Mars has been dusty, and that’s affecting the quality of HiRISE images (just look at the recent images in the catalog and you’ll see they’re not that great). That’s made it hard for me to choose a good one for my blog. I suppose I could go with a grainy image and talk about things like the “cost of real data” and “one person’s noise is another person’s data” (because surely someone will make use of those poor-quality images to track dust clouds, or something). I’m waiting to see where the bright dust falls out on the surface, because I want to show you dust-covered dunes, and then watch how the wind slowly clears them off. It will be a bit like watching snow melt in the spring, if you live in a place that gets snow in the winter.

But first I found a really neat image of missing dunes.

No really.

Sometimes in science, it’s not what you find, but what you don’t find, that matters.

And yeah, it’s a little grainy when you look at full resolution. But you can still see the important bits.

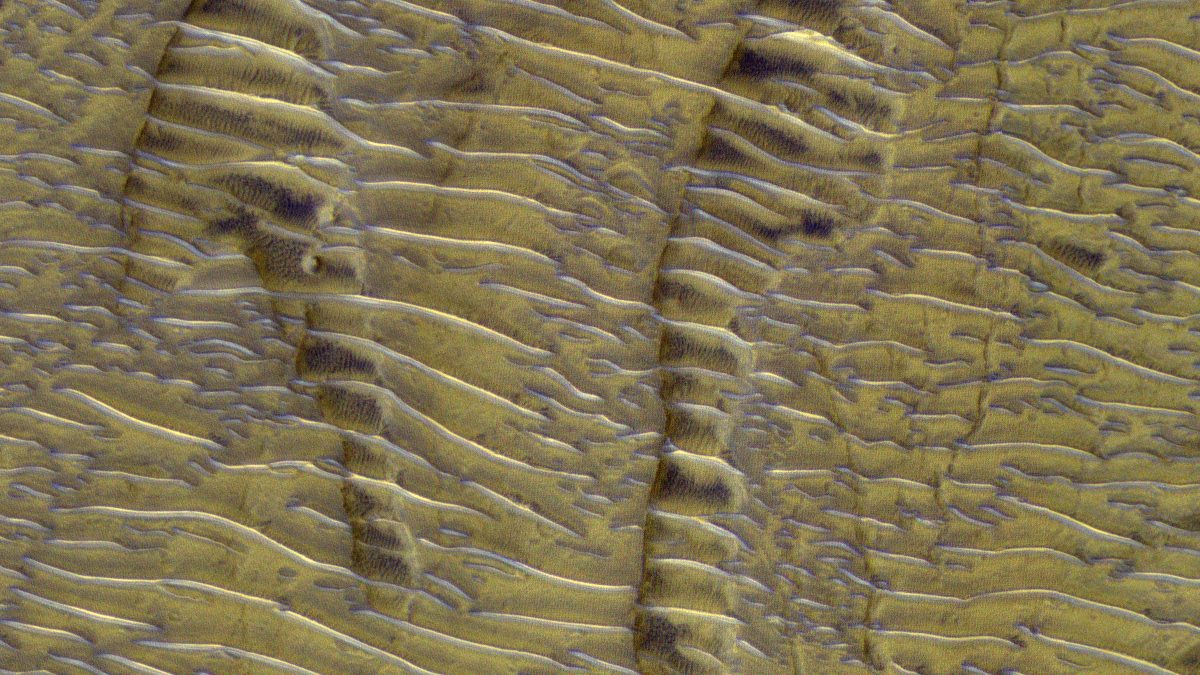

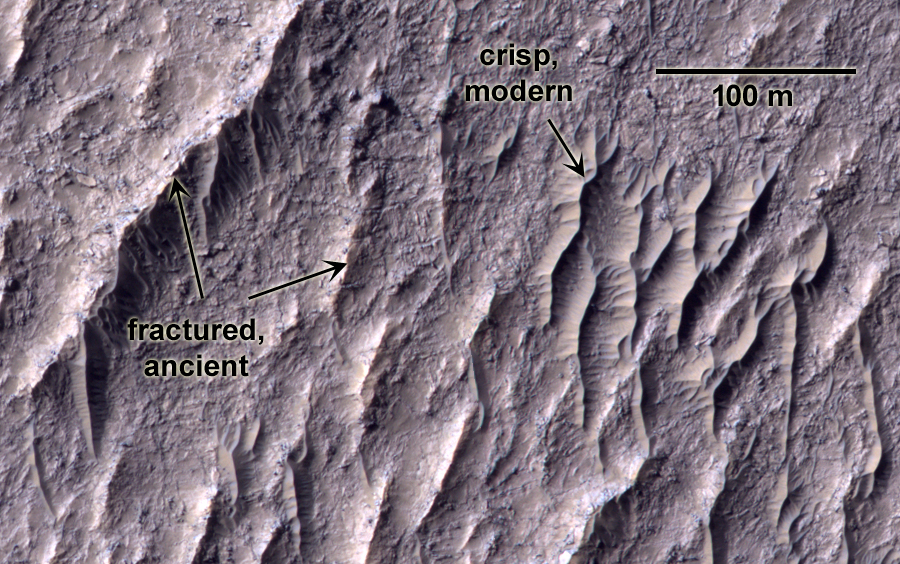

A couple of months ago a paper came out by Day and Catling describing “dune casts”. Here’s a closeup of two of them:

Casts of ancient dunes, view is 600×500 m (0.37×0.31 mi). (HiRISE ESP_055692_1720 NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona)

You’re actually looking at a couple of different windblown things here. You might at first notice the many stripes of ripple-like TARs. Those are relatively young features that are sitting on top of a ~3 billion year old lava flow. The TARs are pretty, but they’re not the target of today’s post.

Etched in the lava flow are two shallow depressions that are ~200 m across. These are the former dunes. The one on the left, in particular, looks quite like a barchan. These depressions are thought to have been the sites of dunes that were sitting around one day, ~3 billion years ago, when a ~6 m (20 ft) deep lava flow inundated them. It couldn’t have been a very energetic flow, or it would have ripped the dunes apart. Instead, it appears to have quietly pooled around the dunes, not quite fully submerging them.

After the lava cooled, the dune sand slowly eroded away. Choked off from their source of sand, the dunes could no longer develop and grow, but rather were resigned to being slowly winnowed away until they were scoured from their dune-shaped pits.

What’s neat about them is they’re about the same size and shape of modern barchans on Mars. They’re larger than most Earth barchans, probably because the air is thinner on Mars (In a very simplistic way of looking at it, sand grains “hop” along the ground. Thinner air allows for longer hops on Mars, and this contributes to making dunes, and possibly ripples, larger than those found on Earth). I think it’s neat that the same processes we see happening on Mars now have been happening there for billions of years in the same way. It tells us that the air on Mars was fairly tenuous as early as 3 billion years ago, which is consistent with the findings of many others.

It’s also a nice reminder that geologic processes on Mars have happened continuously throughout the planet’s history, but what we see on the surface is just a tiny piece of the historical record (Geologists call this the “rock record”, but if you ask them if it’s heavy metal they’ll probably get confused and expound on volcanism, tectonics, and sedimentary deposition. Consider yourself warned.). Most of that record is missing, gone forever, and we can only guess at what was there. But every once in a while, like in these dune casts, we have a pretty good idea of what filled the gaps.